Cushman: Bernardo’s Death Has Made It All Too Clear – It’s Time for Police Reform

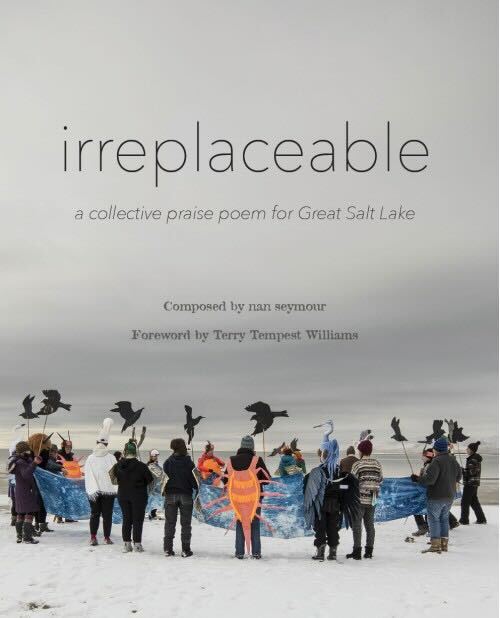

Police in riot gear surround and block in protesters in the streets of Salt Lake City on July 9, 2020. (Photo by Ivana Martinez | Daily Utah Chronicle)

July 21, 2020

The Salt Lake County District Attorney’s decision not to bring criminal charges against the officers who shot and killed Bernardo Palacios-Carbajal sparked protest and civil unrest in Salt Lake City earlier this month, prompting the governor to declare a state of emergency. On May 23, Palacios-Carbajal was running away from police and carrying a gun when p0lice fired 34 rounds at him, striking him in the back 13-15 times. His death and the ruling by District Attorney Gill are a devastating demonstration of Utah’s need for police training reform.

What Is Legal and What Is Just

In a statement regarding District Attorney Sim Gill’s decision, Salt Lake City Mayor, Erin Mendenhall, tried to clarify the district attorney’s reasoning. She explained that all the evidence has shown the two officers in question “acted according to their training and state law regarding the use of lethal force.” Less than a week after Gill announced his decision, a civilian review board ruled the same way, exonerating the officers and declaring their actions lawful. Though Palacios-Carbajal’s death happened in accordance with the law, it fits in with a national trend of excessive force by the police, especially towards Black, Indigenous and people of color. Our communities are still reeling from the murder of George Floyd, which took place just two days after Palacios-Carbajal was killed. National conversations on racial justice, police accountability and judicial reform are ongoing after nearly two months of protests.

The fact that police officers felt they were within their rights to shoot 34 bullets at a Latino suspect, kneel on a Black man’s neck for over eight minutes or kill a Black woman in her own home shows a clear gap in police training on how and when to use force and how to overcome racial bias — both in Utah and nationwide. Gill has even acknowledged that “our standards for deadly force are too broad” and that they create a gap between what is legal and what is just. The role of the police is to protect citizens, but their training and our laws do not promote that goal.

Treatment of Protesters

In the wake of George Floyd’s death, riots and protests began throughout the country — and the treatment of protesters by police has been shocking. In Washington, D.C., law enforcement officers used tear gas to disperse peaceful protesters. An officer in Rhode Island kicked a handcuffed woman in the face. In New York, police shoved a peaceful 75-year-old man to the ground, causing him to bleed from the ear. Across the nation, countless journalists have said police used force against them even after they showed their press badges. Here in Salt Lake City, police repeatedly shoved an old man with a cane, on video, until he fell to the ground. Helicopters circled above the July 9 protests of Gill’s decision, announcing “unlawful assembly, please disperse,” while officers on the ground blocked the streets and prevented protesters from leaving. One protester was arrested and another was body slammed by police after questioning the arrest.

These examples make two things very clear. First, police officers are not trained to care about or protect citizens’ first amendment rights — and second, police are trained to feel so threatened by the public that excessive force is common in tense situations. The police force deems this type of violence acceptable against citizens who cannot exercise self-defense against officers.

The Role of Police Training

Ideas for reform following George Floyd’s murder have been centered around de-escalating situations and having police officers avoid using violence. Avoiding force when possible sounds like common sense, but most states do not include de-escalation tactics in their training, and when the skills are taught — as they are in the Salt Lake City Police Department — it is often “not taught well enough to be retained.” Cops are not only under-trained in that area but are also under-trained in general. Some states only require 400 to 500 hours of training to become a cop. In Salt Lake City, police training lasts longer, totaling 832 hours. For comparison, the average chef or head cook typically accumulates about 4,000 hours of training during their apprenticeship. Police train for less than a quarter of that time, but carry weapons and are authorized to use deadly force.

Police have a stressful and dangerous job. There are certainly times where force is necessary. However, when police are not trained to use that force sparingly and correctly, both officers and citizens are put in danger and avoidable deaths like Palacios-Carbajal’s are more likely to take place. People should not have to be scared of the men and women that are supposed to protect them. It’s worth noting, though, that the use of lethal force hurts officers as well. Human reluctance to kill others is a well-documented phenomenon, and taking someone’s life can be a devastating psychological experience. Police deserve all the training they need to avoid hurting or killing people. The lack of trust in police that results from consistent use of excessive force makes police less effective in their jobs. A 2016 study showed that after reports of police brutality in Milwaukee, 911 calls decreased by 17%. Crime and violence increase when people lose faith in their government and criminal justice system, which makes things more dangerous for officers and for citizens who do not trust the police to resolve conflicts.

When people say that police are violent or racist, it is usually not an attack directed at every individual police officer. Instead, it is a criticism of a pattern of behavior police have exhibited and the systemic failures that allow for those patterns. Training police on how to use force appropriately is not a partisan issue because police brutality affects everyone. It is not exclusive to Minneapolis or Salt Lake City — and solving it will protect Black lives, blue lives and every life in between.