Climate Change and Eco-Fascism in the Dystopian Genre

Agent Smith in “The Matrix,” Thanos in “Avengers: Infinity War,” and Dr. Cayman in “What Happened to Monday” are all examples of eco-fascist villains.

February 13, 2021

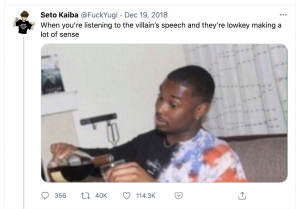

We’ve all seen the trope before: an evil mastermind has justified intentions but extreme methods. Thanos, for example — the supervillain of the Marvel cinematic universe — believes the solution to resource overconsumption is to wipe out half of all living things. His extremism makes him a clear-cut antagonist, but it’s also intended to give him depth and to make viewers rethink just how crazy his motives actually are.

When Thanos vows to kill off every other life form in “Avengers: Infinity War,” he’s addressing the “tragedy of the commons,” a dilemma in which individuals will eventually over-consume a group resource, leading to the collapse of the entire resource so nobody can use it anymore. Is Thanos right — is humanity naturally self-destructive? Is overpopulation ruining the world?

Eco-Fascism in Fiction and Beyond

There’s no doubt that we’re destabilizing our environment. But we’re not all equally accountable for that, as the richest 1% of humans generate over twice as much carbon pollution as the poorest half of all humans. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, where enslaved people mine cobalt for American tech companies, per capita carbon dioxide emissions are just 0.03 tons a year. China, which is often criticized for being the highest polluter worldwide, comes in at 6.86 tons of CO2 per person annually. And here in the United States, per capita CO2 emissions are among the highest in the world at 16.16 tons.

But even these figures can be misleading. Ultra-wealthy groups with private jet trips and multiple homes drive up each country’s average — in stark contrast to the emissions of those who use public transit, consume fewer resources at home, or don’t have shelter at all. Thus, some researchers prefer the tragedy of the “commodity” over the tragedy of the “commons.” The former emphasizes that it is individualist, profit-driven systems that are the problem — not human nature itself and not simply too many humans.

Reducing the existential threat of climate change to a matter of overpopulation — or blaming it on colonized countries that need to develop the infrastructure we already have – is inaccurate, but there’s more to it. It’s a dark line of thinking that can embolden nationalism and authoritarianism.

Guided by this mindset, Western environmentalists of the 19th and 20th centuries argued for eugenics and removed Indigenous peoples to make way for pristine national parks. More recently, white nationalist shooters in Christchurch, New Zealand, and El Paso, Texas called themselves “eco-fascists” and cited environmental concerns as key motivators of their attacks. It’s not unthinkable to imagine governments of the future using a calamity of epic proportions — say, perhaps, global ecosystem collapse — as an excuse to more violently suppress dissent and uphold inequality. Let’s take a look at how this theme shows up in films that explore grim, barren futures.

“The Matrix”

A classic and one of my all-time favorite films, “The Matrix” touches on ecological concerns. Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving) offers a prime example of eco-fascism in his monologue: “Every mammal on this planet instinctively develops a natural equilibrium with the surrounding environment, but you humans do not. Instead, you multiply and multiply, until every resource is consumed. The only way for you to survive is to spread to another area. There is another organism on this planet that follows the same pattern… a virus. Human beings are a disease, a cancer on this planet, you are a plague, and we… are the cure.” Agent Smith has a convincing argument here that parallels the “nature is healing, we are the virus” meme that circulated Twitter at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic last year.

“What Happened to Monday”

This thrilling dystopia on Netflix starring Noomi Rapace, Glenn Close, and Willem Dafoe dives headfirst into eco-fascism. The story begins with scenes of climate change and overpopulation while environmental activist Dr. Nicolette Cayman (Glenn Close) promises to save humanity with a strict one-child policy. The government of 2073 is a totalitarian police state, recklessly abducting and killing people to keep human demands on the environment low. We get glimpses of poor neighborhoods and massive homeless camps contrasted against elegant galas hosted for Cayman’s parliament campaign.

I’m not sure if this juxtaposition was an intentional commentary on hypocrisy within the environmentalist movement or just an easy wealth disparity trope that’s almost ubiquitous in the dystopian genre. Like “Avengers: Infinity War,” the film clearly wants us to sympathize with its villain’s “the ends justify the means” approach. But to Cayman, Thanos, and Agent Smith, the endgame isn’t survival or even the protection of collective resources, as they claim. Their endgame is the protection of their own wealth and authority via systems of exploitation, which is frighteningly recognizable in the real world.

“WALL-E”

Perhaps Pixar’s most obvious social commentary, “WALL-E” is another fun dystopia to take a look at. In “WALL-E” — spoiler alert — the mega-corporation “BnL” wrecks the planet, ejects humans into space while it promises to clean up the mess (but actually makes a pretty pathetic attempt to do so), and then holds its passengers as prisoners. Even when Earth proves to be habitable again, humans are still condemned to space — just because BnL decided that profit-driven destruction of Earth is simply inevitable. Thanos shares that sentiment in his iconic line “I am inevitable.”

This is what eco-fascists share: the belief that humanity is inherently and inescapably doomed, so we must sacrifice the freedoms or even the lives of one group to keep another more important group alive. In dystopian films and in reality, this mentality creates frightening (but perhaps predictable) Machiavellian environmentalists who mistake the current belief systems of one region for biological human nature.

The Evolving Dystopian Genre

As climate change intensifies around the world, it will become a more and more prominent theme in the media we consume. So, I think we can expect to see more environmental philosophy in future dystopias (water scarcity is no longer the far-off hellscape of “Mad Max: Fury Road,” for example — it’s already happening) but I hope we’ll see new types of climate change commentaries, too. There’s an opportunity here for filmmakers to tell stories that are more imaginative in their explorations of how human culture could potentially shift in response to environmental collapses. We’re a diverse and adaptive species, and maybe it’s time that’s more uniquely explored in the dystopia genre.