Kincart & Shadley: Reducing Child Poverty with Romney’s Family Security Act

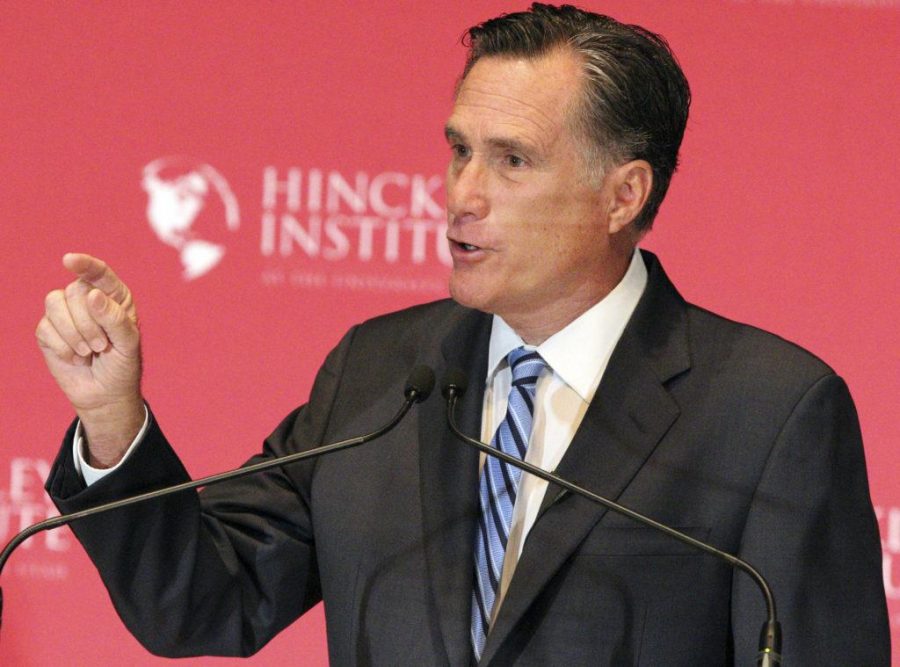

Former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney gives a speech on the state of the Republican nomination for president at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Thursday, March, 3, 2016. (Tara Lincoln, Daily Utah Chronicle)

March 18, 2021

Despite poverty in America steadily decreasing over the past five years, poverty among children was still as high as 18.7% before the pandemic. Prohibitively expensive child care forces parents into unemployment or underemployment. The pandemic, which has increased rates of child poverty, has led to even higher unemployment rates. With 32-42% of the jobs lost to the pandemic being gone forever, America stands at an inflection point of childhood poverty. Left unchecked, rates will continue to rise.

Luckily, Sen. Mitt Romney and President Joe Biden have each unveiled their own plans to reduce child poverty. While President Biden’s plan would provide greater assistance to low-income families, it would only do so for a single year. Meanwhile, by cutting a handful of programs like TANF, SNAP, and the Child Tax Credit, Romney’s plan would assist all families — regardless of income, in perpetuity. In doing so, Romney’s Family Security Act (FSA) would compensate American families for the valuable work of parenting.

The FSA would provide $350 per month for children under six and $250 per month for children between the ages of six and seventeen. Parents with multiple children could receive up to $1,250 per month, meaning families with five kids between the ages of six and seventeen would receive the full amount. In Utah, where we have the largest average household size in the nation, parents would be able to navigate the financial uncertainty of the pandemic much more adeptly.

One of those parents, Craig Watts, a single father of three elementary-school-aged children, often has difficulty affording “unexpected expenses.” Those expenses have become more troubling after losing his teaching job in Salt Lake City due to COVID-19. By disentangling the ability to care for your kids from your employment status, the FSA would provide Watts, and parents like him, with assistance to take care of his children.

If paying people to take care of their children would reduce child poverty by one-third, as the FSA would, why has America failed to do so throughout its history? In the past, jobs traditionally held by women have not been properly compensated for the economic value that they create. This can be seen in female-dominated industries and any industry that has to do with homemaking — teaching, food service, and cleaning services. These industries receive less pay than male-dominated industries (like STEM).

Similarly, women are more likely than men to be affected by child care duties at home and eight times more likely to manage their children’s schedules. Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s book, The Two-Income Trap, explains how household duties are expected of and traditionally accomplished by women — that is, until women started entering the workforce. When women work outside of the home, families spend more on child care and commuting. However, these extra costs aren’t always covered by the second income. The FSA would fill this gap and compensate parents for the expenses of raising children and ultimately allow more people to enter the workforce.

Parents without childcare spend, between the two of them, an average of 30 hours per week caring for children under six. Those parents who have opted to outsource that care spend roughly $500 per month. As a result, parents are often overworked, underpaid and unable to provide for their children, leading to increased rates of poverty. Matthew Weinstein, the State Priorities Partnership Director of Voices for Utah Children, argues that the FSA would “reduce the poverty rate substantially.” That reduction makes a “huge difference” in kids’ health, parents’ health, graduation rates, college enrollment rates and post-secondary degree attainment. Parenting is difficult, important work, made even more challenging when facing the grueling effects of poverty.

While the FSA would undoubtedly provide the majority of American families with greater financial security, there are legitimate questions about how it fits into overarching family policy. Part of Romney’s plan to pay for the FSA includes cutting Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). As Weinstein notes, “Utah receives $77 million a year in funds from TANF, and $65 million of that goes into programs other than cash assistance, including child care and job training.” These are programs that “need to keep going,” otherwise, Utah families with the lowest incomes will not end up any better, and possibly end up worse.

As America’s legislators look to fund universal programs, they need to keep in mind the equitable distribution of benefits. Still, the positive effects of a long-term universal child allowance outweigh the negatives of the FSA by providing families with a genuine route to escape intergenerational poverty. So often in the American welfare system, parents are poorly incentivized by what Weinstein calls “benefit cliffs,” were accepting a raise at work may cause the family to lose all of their assistance. Consequently, families tend to turn down these sorts of opportunities and remain trapped in lower-earning jobs. However, when benefits are given to everyone, regardless of their income level, the incentives to increase one’s income are restored and those increases will correlate with increases in the quality of life.

While the pandemic and ensuing unemployment have made it difficult for Watts to pay for groceries and rent, it’s afforded him the unique opportunity to spend meaningful time with his kids. Many American parents, like Watts, have had to work multiple jobs to make ends meet — sacrificing their nights and weekends away from home. The FSA would provide parents with the opportunity to work less without having to face the effects of poverty. After all, “an hour spent working is an hour less [with] my kids.”