Kincart: We Need More Focus on the Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women Crisis

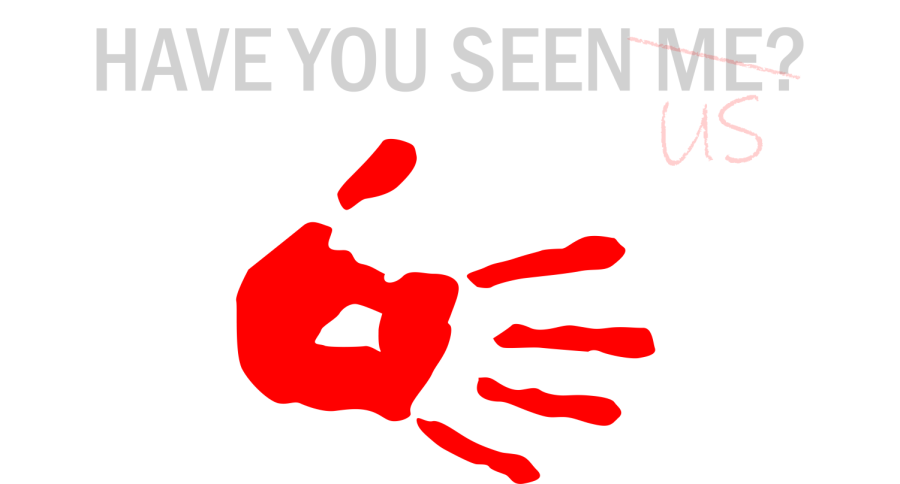

(Graphic by Claire Peterson | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

October 5, 2021

Gabby Petito’s case has dominated the media. Every time I checked social media, I found posts related to the case. And while atrocious, stories like Gabby’s are much more common among Indigenous women, but their stories are seldom talked about.

The U.S. Department of Justice finds that American Indian women face murder rates 10 times the national average. On a more local note, Utah and Salt Lake rank in the top 10 U.S. states and cities for the highest amount of murdered and missing Indigenous women and girl cases.

When I lived in South Dakota, our annual Women’s March included speeches from Indigenous women bringing attention to the issue. However, the stories of murdered and missing Indigenous women are constantly buried under narratives of missing white women. We need to act on the murdered and missing Indigenous women crisis, as it’s a failure of the women’s rights movement to not address this discourse.

Indigenous women are murdered and go missing at alarming rates, but the statistics don’t tell the whole story.

Law enforcement agencies don’t always collect the race and ethnicity of victims. When a race isn’t reported, some database systems default to white.

In 2016, The Urban Indian Health Institute in Seattle conducted a survey showing that 5,712 Alaska Native and American Indian women and girls were reported missing. But of those 5,172, only 116 were registered in the Department of Justice database.

Professor Elizabeth Archuleta, the Associate Chair in the Division of Ethnic Studies at the University of Utah, explained that Native women such as Annita Lucchesi and Abigail Echo-Hawk collect the stories of missing Indigenous women.

Professor Archuleta furthered that the underlying sense of trust shared between these women is crucial to data collection. “Data collection needs to be taken with a grain of salt depending on who’s collecting the data and how it’s presented,” she said.

Jurisdictional issues between tribal and non-tribal land also complicate police action on reported cases. According to Professor Archuleta, “jurisdictional issues refer to crimes that happen on reservation lands and whether tribes have the right to prosecute nonnatives.” But a recent Supreme Court decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma could restore jurisdictional rights to reservations. This will put more focus on the murdered and missing indigenous women and girls crisis.

But, currently, white narratives remain dominant when it comes to missing women. Petito’s case eventually became the main story for several popular news outlets such as The Washington Post, USA Today, CNN and Fox News. These stories continue garnering attention, in part, because news organizations are “disproportionately white” environments. White women in media resonate with the stories of other white women and amplify them.

These reporting habits have been coined “missing white woman syndrome” by Gwen Ifill. This disparity can be attributed to racism.

The media, and we as consumers, view white women as “good people” while seeing people of color as “risk-takers” and therefore bringing about their own tragedy. Professor Archuleta finds that this stereotype is a common misconception native women face.

We need to acknowledge the complex and unjust history experienced by native people. “The history of settler colonialism and violence that’s been inflicted on native peoples’ land dispossession and the assimilation tactics [of] the boarding school era,” Professor Archuleta says paint “a much bigger and complicated picture.”

Native women shouldn’t be reduced to harmful stereotypes — this is inherently not feminist. These stereotypes hinder the push towards finding missing and murdered indigenous women. And we can do more aside from dismantling our conception of harmful stereotypes that perpetuate these injustices.

Journalists need to be more careful in their reporting of missing women. Unnecessary racialization contributes to the perpetuation of missing white woman syndrome. We can amplify the stories of murdered and missing indigenous women through social media.

Professor Archuleta credits native TikTok and native Facebook pages with doing some of this work. As consumers, we play a role in getting the media to shift from the dominant white woman narrative. If we interact with these posts on social media, we can shift media attention.

But on a broader scale, we need to recognize that this issue is a feminist issue. We need to see indigenous women’s issues as women’s issues. The murdered and missing indigenous women crisis needs to be a central pillar of the women’s movement. A lot of our inaction when it comes to the murdered and missing indigenous women crisis stems from a lack of knowledge on the issue. As Archuleta mentioned, “once students learn about [these issues], then they know to look for it … it becomes a way for students to become allies.”

Austin Nicholas Draper • Nov 8, 2021 at 10:51 pm

How can one help? Are there any organizations I can donate to? Bills I can sign? Senators I can contact? Places to go to?