Native American Heritage Month: Recognizing History and Moving Forward

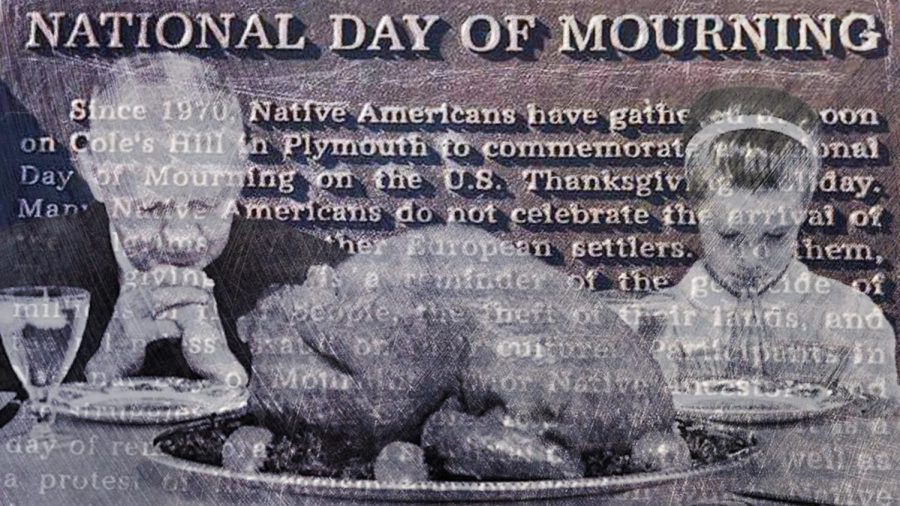

(Graphic by Cyan Larson | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

November 25, 2021

The Historical Untruths of Thanksgiving

In the United States, students learn the 1621 harvest feast that started Thanksgiving was a peaceful sharing of food between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag people at Plymouth. In fact, it was a holiday resulting in the genocide of Native Americans and the disruption of the Native American lifestyle.

The teaching of Thanksgiving often focuses on the English settlers — history books portray them as colonizing the land and creating the first real civilization here. However, Native Americans had occupied the continent for centuries before.

Carrying diseases like smallpox, measles and influenza, the Pilgrims created an epidemic killing approximately 90% of the Native American population in the Americas.

Historian David Silverman wrote a book called “This Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving,” which focuses on the Wampanoag people and the historically accurate depiction of this autumn holiday.

In an interview with Smithsonian Magazine, Silverman said, “[The Wampanoag people] felt like their people’s history as they understood it was being misrepresented. They felt that not only their classes, but society in general was making light of historical trauma which weighs around their neck like a millstone.”

Beyond the initial 1621 feast, the mistreatment of Native Americans at the hands of Europeans and outsiders only continued. Their treaties were betrayed, they were forced onto reservations and had their heritage, resources and land were stolen from them.

As a testament to their ancestors, some modern Native Americans hold a Day of Mourning on Thanksgiving. They host speeches, often fast from sundown the night before to sundown the day of and share their stories as a way to remember their ancestors.

Intergenerational Trauma: Boarding Schools

Boarding schools operated by the U.S. government separated Native children from their families and stripped them of their culture through forced assimilation to Western clothing, language, religion and values.

Such schools were widespread, with 60 schools housing 6,200 Native American students by the 1880s. The motto of the Carlisle Indian School, one of the most well-known, was “Kill the Indian, save the man.”

In a community conversation organized by the Bennion Center at the University of Utah on Wednesday, Nov. 17, Native people in the U community were invited to discuss the impact of these traumatic moments, as others joined in reflecting and listening.

Franci Taylor, executive director of the American Indian Resource Center at the U, opened up the discussion by inviting listeners to put themselves in the shoes of the children who were taken to these boarding schools where they were abused and forced to assimilate.

“Let’s say you’re four years old and this group of unfriendly, non-smiling Swedes came into your home and took you out when you didn’t speak any Swedish … and they took you away for days on a train … when you got to this place, the first thing they did was take all of those gifts your parents had given you, the clothing that your grandma made with for you with great love, and in front of you, burned it,” Taylor said.

Taylor continued on to say the children were scrubbed with bleach.

“They took before and after pictures … the dirty Indian versus the cleaned up, assimilated child,” Taylor said. “You were beaten for speaking your language. You were denied food.”

These institutions, ripe with physical, sexual and emotional abuse, alienated, traumatized and sometimes killed the Native children who attended.

“My culture keeps hair … if you cut your hair, it meant everyone in your family was dead,” Taylor said. “And boys and girls both have their hair cut immediately upon getting to these institutions. So of course they thought everyone, everything that they love was now gone.”

Ben Crane, another community member in attendance at the discussion, drew parallels between the treatment of indigenous people in the U.S. and Canada, where he is originally from. He described the horror felt at the discoveries of thousands of unmarked graves at Canadian residential boarding schools, and the impact of intergenerational trauma he has felt in his own life at the hands of these schools.

“I was there in Canada when these discoveries were happening all summer every two weeks,” Crane said. “It was brutal, because they were discovering these bodies of these kids.”

Crane comes from a long line of survivors of Indian residential schools.

“My father, his parents, my grandparents, possibly my great great grandparents … and it’s really impacted my community in a very violent, traumatic way,” Crane said. “These are legacies that are still very much prevalent in a lot of First Nation communities … alcoholism, violence, abuse, substance addiction, homelessness, the missing and murdered indigenous peoples.”

“We’re not history”: Increasing Awareness on Campus

Two students on the U’s campus who have been fighting to celebrate and support Native people right now are Brook Miller and Dana Yazzie, co-chairs of the Indigenous Student Association and Allies at the U.

The idea for the organization was born of a conversation between the two students this semester, when discussing the hype surrounding the case of Gabby Petitio, a 22-year-old white woman who went missing.

“It was just all over the news, but in the Native American community, there are tons of missing and murdered women who go missing … they get murdered 10 times the national average, there’s someone missing every month,” Miller said. “It was just very confusing to us because it was like why does this one girl get all the attention when all of our people, all of our sisters, go missing and no one cares about them?”

Yazzie said the push to start raising awareness of Native issues on campus also came from her experiences talking to non-Native people and realizing just how little people know. In one instance, Yazzie recalls meeting a student on campus who just recently found out the Utes are a Native American tribe.

“She’s like, ‘I just found out that the Utes are an actual, like, Native American tribe … when I first came here, I thought Ute was an animal, because most school mascots are based off of animals,’” Yazzie said. “[Her friend] said ‘Yeah, I didn’t know what a Ute was until I saw that statue.’ And then they asked, ‘Are there actual Utes that come to this school?’”

Miller pointed out the widespread lack of knowledge of indigenous cultures and issues on campus is ironic, considering the U mascot is named after a Native American tribe.

“A lot of [Native] students [in ISAA] felt like they were invisible, on a campus that’s based off of our culture,” Miller said.

In celebration of Native American Heritage Month, ISAA prepared a display case on the first floor of the Marriott Library, something the club had been working on since October.

Each item in the display is accompanied with informative placards explaining its meaning. Something especially important to the students was emphasizing Native culture is not just something from history, but rather something continuing to thrive today.

In the display, they incorporated multiple pieces of art created by current members of ISAA.

Miller said deciding what to put in the display case was a process they started by presenting the opportunity to ISAA members, and making the most of the talents available to them and incorporating as many different tribes as possible. The display includes artwork by Yazzie, along with beadwork and a ribbon skirt made by other members of the ISAA tribal council.

“We just really wanted to put pieces in there that represented our students…there’s like a little blurb about them, like ‘Dina Mitchell made this ribbon dress, she’s a kinesiology major,’” Miller said. “It’s to show that Native Americans are not history. Because when you go to class and you learn about them … it’s all in the past … like, Native Americans used to wear turquoise, we still do. Used to make beadwork. We still do.”

Miller said it was important to include student work in the display to emphasize the existence of Native American culture in the modern day.

“It’s not just like this cool display of all Native American artifacts that we dug out,” Miller said. “Like, no, these are modern and these were made by students recently.”

In addition to these current pieces, and some of those “dug up” artifacts, the students of ISAA also used the display case as an opportunity to raise awareness on the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women crisis. In 2020, the National Crime Information Center reported 5,295 records for missing American Indian women and girls.

Preparing this display case is something Miller and Yazzie describe as both “fulfilling” and “heavy.”

“There’s a red dress in there, and there’s pictures of actual girls who are missing and I think for that it was really kind of hard … we want it to be respectful, so we got permission, directly from three of the girls’ or womens’ families to use their picture in the display case,” Yazzie said. “They were very grateful and very excited to spread the awareness because [knowledge of] MMIW is concentrated within the Native American community.”

Miller and Yazzie said they find joy in witnessing they are making a difference, whether through making Native students feel less invisible, or knowing they were the ones to educate non-Native people on an issue they were not previously aware of.

“I think one of my favorite things to do lately is watch people walk by the cases,” Yazzie said. “And then like even though maybe two or three people stopped specifically to look at the MMIW case, it’s like that’s one more person that knows.”

The students of ISAA continued to raise awareness for MMIW on Monday, Nov. 15, by hanging up red dresses around campus. These dresses appeared around the student union and the library, on hangers and on bulletin boards, accompanied by tags explaining what the dresses are and dedicating them to a woman who is gone.

In addition to highlighting important Native issues, ISAA has also been providing fun ways to celebrate Native culture, from a dance performance on Nov. 18 to a beading workshop to the upcoming Friendsgiving Dinner.

The club meets every Friday at 4:30 p.m. at the American Indian Resource Center, past the Legacy Bridge. The club regularly posts information about events on their Instagram account. The club welcomes everyone.

In terms of Native heritage, Miller said she is most proud of the ability of Native people to survive after all they have endured.

“It amazes me that we’re still here, because of all of the terrible things that happen to us as indigenous people … we were sought after and murdered, sold, raped, killed, like it was just like one thing after another,” Miller said. “And she [author] is like, ‘by such slender threads, we did persist.’ And I cried when I read that line, because it just reminded me … of all of the hardship and all of the trials that our ancestors had to go through … but by such slender threads, we did persist.”

Miller said there is nothing that can take a native community down.

“Everything in our culture I think is beautiful,” Miller said. “From our blankets to our jewelry to the way we treat our grandmothers to the way they treat us.”

For media to consume this month, Miller recommends the book ”The Beginning and End of Rape” by Sarah Deer. For something lighter, Yazzie recommends the book ”Navajos Wear Nikes” or watching the iconic ”Smoke Signals.”