Buening: Collective Memory Should Serve Everyone

March 24, 2022

As the Russia-Ukraine war wages and tensions continue to rise, former U.S. Secretary of Labor Robert Reich highlighted the role of collective memory within the issue. In a Guardian column, he said that “those who have fought ground and air wars know war is hell. Subsequent generations tend to forget.” Today, many Americans with no direct experience of war continue to misconstrue it. They see our vast military strength as something to prize above all else, but military strength exists to be utilized. War is more than an egotistical claim to victory or power struggle — it causes mass destruction.

How can we fully comprehend this destructive impact when many of us are limited by previous experience and collective memory? Our inexperience can allow oppression to seem more like an abstraction — something disassociated or insufficiently factual — than a reality at times. We can consider our collective memory a hyperobject, a “phenomenon so vast that it is beyond human comprehension.” What we maintain of history through collective memory has a profound impact on the world around us. What lessons have we forgotten by allowing events like the Vietnam war to fade from our collective memory? To establish sustainable, informed inter-generational values, we need to mold our collective memory into something representative of everyone’s historical experiences, not just the most privileged.

What is Collective Memory?

Collective memory is understood as “reactive to the intrusion of traumatic experience from the past upon the present,” and comprises social group identities constructed from narratives and traditions. In the U.S., events like 9/11 have become a somber staple of our history and national identity. Generations born after the event continue to experience impacts from it — emotional, tangible and otherwise. These memories and their accompanying narratives, passed down generationally through oral pathways, literature and education, impact how we approach today’s societal injustices. Because history has defined the present day, these injustices act as remnants of the past. What we do or don’t retain from the past continues to influence people today.

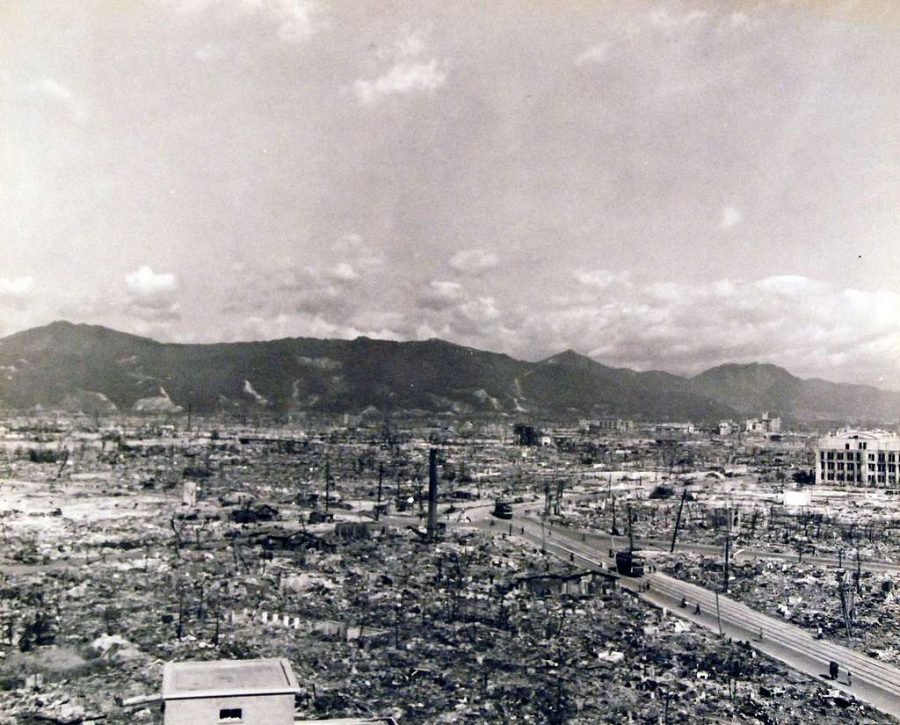

Collective national memories vary and change over time. Most Americans remember the bombing of Hiroshima as a critical event in World War II. However, older and younger populations disagree about its significance. Many older adults view the bombing as a positive, citing that it ended the war and spared American lives. But most younger adults today see the nuclear bombings as devastating and immoral as it killed and injured hundreds of thousands of people. Today, young people will carry with them the collective memories of a global pandemic and the explosion of social media influence, for better or for worse. In an era of mass-reporting disaster coverage, we see the expansion of our ability to create collective memories.

As Scientific American said, “To understand a country’s memories is to grasp something essential about their national identity and outlook.” Essentially, what we cherish in collective memory is a strong determinant of our current and future values.

Unequal Representation Within Collective Memory

Because of how our collective memory influences our perspectives, we must remain wary of historical misrepresentations. Viewing historical events through the lens of present-day privilege causes damage. In the context of the Russia-Ukraine war, the historically colonialist and racist paradigms of western society have contributed to bigotry in media coverage and aid distribution. News correspondents from the west have aired statements like, “The unthinkable has happened … this is not a developing, third-world nation; this is Europe!” Such statements show profound, deep-seated biases founded in warped collective memories. If we look at history and take from it that conflict is inherent to some more “deserving” places, like the Middle East, something is wrong. And while refugees flood out of Ukraine, Black populations in the country have experienced blatant violence and racism at borders and checkpoints.

For those of us on the other side of the world watching this conflict, we may experience the impacts of higher gas prices and flooded media headlines. But we lack empathy for the war’s reality when we fail to respect its severity. This represents a fault of predominantly western collective memories, where we experience a larger issue. Within the U.S., historically marginalized communities continue to face disproportionate inequalities because of our failure to recognize their condition.

Moving Away From Self-Centered Mentalities

The values of our nation’s collective memory must be expanded beyond the self-interests of the few. Some of the most necessary solutions remain controversial. For example, the narratives we pose in education go a long way in determining how young people approach injustice. Many people like to view racism as something characteristic of the past, without realizing that the Civil Rights Movement was an event in recent history. Instigating practices like Critical Race Theory in education could help absolve such misguided notions. We need to prioritize the contributions of underrepresented groups to history, perhaps by expanding upon women’s roles, teaching Indigenous histories and applying those lessons to the present day.

Our collective memory must no longer fall victim to society’s hierarchies. Our collective self-esteem doesn’t have to rest upon a refusal to acknowledge past failures. Rather, it should rest upon moral character — which can only be achieved through reparations to impacted communities. That requires us to step outside of our comfort zones and preconceived worldviews.