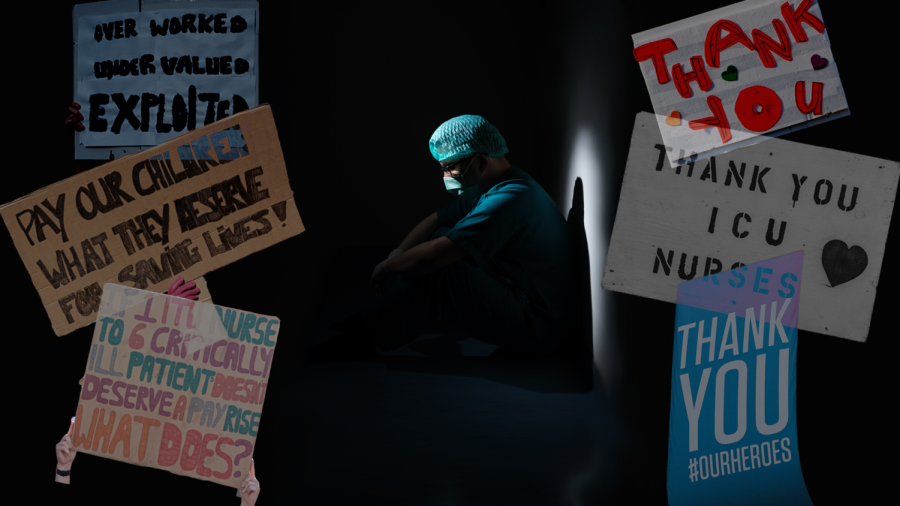

Utah Nurses Speak Out about Working Conditions, Lack of Response from Hospital Administrations

(Design by Claire Peterson | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

June 25, 2022

“Heroes Work Here” signs have filled the University of Utah Hospital since April 2020. Yet, according to the heroes themselves, they don’t get fair wages, adequate time off or an answer to their concerns, but they do get pizza parties.

With the demands created by the COVID-19 pandemic, Utah’s healthcare system has seen a severe staffing shortage. In March 2022, approximately 20 military medical personnel came to the U Hospital to address direct patient care needs for 30 days, and the following month, the U College of Nursing expanded its enrollment by 25% to compensate for the nursing shortage.

What they haven’t done, according to three anonymous nurses and one healthcare assistant, is care for their own existing staff.

Patient Safety

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, stress mounted and healthcare expectations changed. According to an obstetrics nurse formerly with Intermountain, nurses thought the situation was temporary, but it soon became clear that their ability to provide adequate patient care was greatly compromised.

She said it felt like nurses were frogs in a pot, where the water temperature was slowly turned up. The water couldn’t be boiling — they would feel it, and hop right out.

“They were just hoping we didn’t notice that they were cooking us to death,” she said.

One nurse from the Intermountain Medical Center said it is scary and stressful to not be able to give the care they went into nursing to give.

“We don’t eat, we don’t pee and we barely drink water,” said the nurse currently working at IMC. “And at the same time, there’s a lot of pressure from hospitals to do more and to be better and to listen to your patients.”

Bonuses that were typically guaranteed every Christmas became based on units meeting certain marks of patient satisfaction. According to the IMC nurse, this is difficult to achieve when they are required to take on more patients than they can adequately care for, making some scared of losing their license.

For the former Intermountain nurse, not being able to provide adequate care is not just risking one’s license — it is something the nurse has to live with for the rest of their life.

“I remember, they’d say … it’s going to be crisis standards of care, meaning that we wouldn’t be held liable if we made an honest mistake and someone got hurt,” she said. “And I thought, I still have to live with myself. Like, if I hurt someone, I may not end up losing my license, but I will carry that with me forever knowing that I made a mistake that could have been prevented.”

The current IMC nurse said in places like California, where there are unions at many of its hospitals, there is a staff-to-patient ratio cap, ensuring nurses can speak up if they feel the amount of patients they are given is unsafe.

“Right now we’re at the bare minimum staffing, skeleton style,” she said. “ICU nurses are taking two to three patients, when that’s a job that you’ve signed up for to be one on one, maybe you have two if they’re more stable. It’s just not possible to safely keep people alive.”

Madi Gallegos, a staffing coordinator at the University of Utah Hospital and health care assistant, said the number one concern right now is patient safety — in the ICU, a nurse should never have more than two patients.

“ICU patients are critical care and they need more attention and they deserve to have a nurse that’s just there for them,” she said. “All patients deserve to be safe.”

Gallegos said staff is allocated based on predetermined, approved ratios. For example, the ratio for ICUs is two patients to one nurse, whereas the patient to nurse ratio in acute care is supposed to be five patients to one nurse, or four to one if it is a more critical unit.

“They tell us how many nurses they have coming on, how many they’re down, and then based on those ratios is where we allocate our own staff, which is the float pool staff,” Gallegos said. “Some nights there’s more than others. Some days there’s more than others, so we just have to go on: the highest ratio gets the nurse. But that could be like by 0.1 that they’re the highest ratio.”

Staffers coordinate with the nursing supervisor every day to make the safest scenario possible.

“But we can’t create more nurses, like we only have what’s coming on,” Gallegos said.

The former Intermountain nurse said in some places, even full-time employees are required to pick up a call shift.

“If you work at night, you don’t sleep because you just anticipate your phone’s gonna ring,” she said.

One of her friends was a part-time charge nurse, who was called in to work for every call shift — according to her, she essentially was working full time without reaping any of the benefits. This also leads to overworked and exhausted caretakers, putting patients’ safety at risk.

‘We Don’t get Paid Enough’

According to the IMC nurse, in the past few months, Veterans Affairs, U Health and IHC announced a 6% pay increase for caregivers. However, as the cost of living in Utah has increased, in some cases, this raise actually presents itself as a pay cut.

“For my pay, that gives me $1.60 an hour more, when my rent just went up $500 a month,” the current IMC nurse said.

Usually, pay increases came with individual merit — coming in early, doing extra work and having goals normally meant a raise.

“Today I trained a new nurse and she was making almost $2 more than I an hour because she’s coming in as a new nurse in 2022, and they’ve increased the pay,” she said. “But for the nurses that have stayed, we have not gotten an increase. So that was really difficult to swallow.”

Gallegos said some people think health care assistants aren’t necessary, but they are. They’re also receiving inadequate pay.

“I worked at the U for five years, and they’re getting hired for more than I get paid,” she said. “So they’re spending more money on hiring new people instead of retaining their own employees.”

The United UT RNs Instagram account has been helpful in fostering a community with pay transparency, according to the IMC nurse. She said there does not seem to be a rhyme or reason to the amount everyone is paid.

“It’s incredible how different everyone is paid regardless of their tenure — if they’ve been there for 10 years or two years,” she said. “Sometimes people who have been there less time are making more, and men are making more than women.”

According to her, at IMC, people are scared of getting fired, so they don’t discuss their wages.

Over the course of the pandemic, Utah hospitals started incentivizing nurses to come in on their days off, with some getting $2,500 a shift.

“What happens is, we all need money because everything is so expensive right now, we don’t get paid enough,” she said. “So we come in and we’re just so burnt out.”

She is worried this is the cause of many nurses fleeing and is concerned about a potential “mass exodus” of nurses.

“I’m feeling it, I’m hearing it, I’m seeing it, and I think it’s gonna get really bad,” she said. “To the point where I’m really nervous for my patients, I’m really nervous to go to work.”

With “burnout” — what some workers are calling exploitation as a matter of praxis — feeling under-appreciated and a host of other problems, nurses are experiencing worsening mental health. According to the IMC nurse, not only can they not afford services like counseling, but therapists have limited spots open.

“We have a lot of nurses on medications to help them get through the day and the stress,” she said. “Almost everyone I know is on a sleep medication just so they can go to sleep at night and turn off their brain. I don’t feel like there’s a healthy balance for any of the nurses I know.”

Even on their days off, nurses’ phones are inundated with incentives and pleas to come in to help.

“For someone like me, who’s very empathetic and wants to help and loves my job, I want to come in, but lately I’ve stopped because I no longer can,” she said. “I have nothing left to give, and I have to find my mental health again.”

Striking to be Heard

Nurses have been sending anonymous letters to hospital administrations advocating for themselves. Some wrote and published an online petition in March — which has reached 4,188 signatures as of June 24 — including a market analysis of pay in comparable housing markets. They issued a press release, conducted some interviews and organized a rally at the Utah State Capitol.

According to one U Health clinical nurse and organizer with Unite UT RNs, they did not receive any official acknowledgement of the petition. In April, U Health administration sent out a survey to its employees to address their top concerns.

According to a story posted by the Unite UT RNs Instagram account, Chief Nursing Officer Tracey Nixon visited a unit, saying there will be half a dozen executive retreats to talk about wages.

A member of human resources at the U Hospital told KSL they are aware of the current issues and are rolling out new programs regarding compensation and mental health.

Over the course of eight days, starting June 17, the Chronicle reached out to one member of U Health leadership via email and various members of public relations via email and phone calls. The Chronicle was in touch with the media relations team but was not able to receive a comment by the publication date.

The Chronicle additionally reached out to Intermountain Health over the same time period, with an email to a member of leadership and an email and calls to their media relations team. The Chronicle got in contact with this team, but was directed to speak to someone from the Utah Hospitals Association, who was unable to provide a comment.

The anonymous IMC nurse said there has been no response from IHC regarding their concerns, but she thinks the U’s response is promising. The U Health nurse said their communication has been met with silence from U Health administration, leaving staff with unacknowledged concerns.

So, they are organizing an overtime strike.

RNs, CNAs and health care assistants are participating in the strike from July 9-22, where they will pick up fewer shifts than they routinely do. Via a poll in the first week of June, the Unite UT RNs Instagram account received a count of 100-120 nurses committed to the strike.

The U Health nurse said people are sometimes working 60-72 hours a week to make ends meet, because wages are low — hospitals are relying on people taking extra shifts to keep the hospital running.

“That is not sustainable for the hospital and that’s not sustainable for individuals,” he said. “It’s not a way to staff your facility. It’s not a way to compensate people adequately, by basically forcing your hand and having them pick up extra shifts.”

Overtime, according to the IMC nurse, is not a staffing solution for a healthy unit. A majority of the week, nurses get texts that the hospital is in a red status, asking nurses to come in for double time.

“No one’s responding to these text messages anymore,” she said. “We’re done. We’re burnt out. We can no longer pick up these extra shifts. We don’t want to.”

Hospitals have been attempting to address this in different ways — bringing in travel nurses and nurses from other countries and floating nurses around to different units.

Travel nurses, who work through an agency and would make thousands more per month than the already staffed nurses, do not know any other staff members and are not acquainted with where anything is, according to the IMC nurse.

Floating nurses around is a safety issue — when it comes down to it, a nurse is not just a nurse.

“You specialize, generally, and you start to really gain experience and understanding and knowledge on certain issues that happen with patients’ medications,” she said. “I mean, as a patient, I would be nervous to be in the hospital right now. And I wouldn’t want my family to be in the hospital right now. And that’s terrifying.”

What’s difficult about this, according to the former Intermountain nurse, is that she would trust her fellow nurses with her life, her children. But she said when these caretakers are abused and mistreated, patient care is impacted.

The former Intermountain nurse said after pushback from nurses, the system was changed to make the then floater nurses into assistants — they would clean respirators, help in an emergency and do what was needed of them.

“I don’t know where anything is, if they need something in an emergency,” she said. “I may not have badge access to their medication room. I don’t know how to hang certain medication. Like even that felt unsafe, but it felt better than being forced to actually be the primary nurse taking care of people that I have no idea what was going on with them, or how to care for them.”

When floating became mandatory, a nurse had to go home sick if they did not want to float. This would require the next person to take on that responsibility, and many did not feel comfortable doing that to their friends.

The former IMC nurse said nurses bond through shared traumatic experiences. According to her, hospitals rely on nurses being willing to do anything to help their colleagues out.

On paper, the hospital was fully staffed. What the algorithms and spreadsheets don’t account for, however, is the acuity and type of care that some patients require.

“The fact that there was this person on a computer who had never been on our unit saying, ‘Hey, I’m sorry, but you know, you guys should be able to function with five nurses instead of seven or whatever,’ — that was so frustrating,” she said.

According to the current IMC nurse, “safe staffing saves lives.”

“Better pay saves lives, literally, because we have our experienced nurses on the floor, taking care of the patients, that know what they’re doing,” she said. “And you can’t put a price to an experienced nurse. They know so much more than a brand new nurse who’s coming in.”

Moving Forward

The current IMC nurse said her colleagues who left have done so because of the staffing, the scheduling and the pay — not because they don’t love what they do.

“If they could offer us better hourly wages and safe staffing ratios, we wouldn’t be leaving the bedside and we wouldn’t have this crisis,” she said.

Beyond the staffing shortage and the strike, the IMC nurse said healthcare as it stands today needs massive changes.

“I really feel like we’re at this crossroads of the healthcare system collapsing, because a hospital cannot run without a nurse,” she said. “Nothing will operate without these caregivers.”

Without a direct line of communication with a manager or CEO who can effect this change, she feels like she has no control over the situation.

She feels ready to quit everyday. Most of the nurses who are leaving, according to her, are the experienced ones.

So, when emergencies happen, and codes are called, these brand new nurses don’t know how to handle the situation as quickly as a more experienced nurse. This, to the IMC nurse, is terrifying, and makes her not want to go to work.

“You want those nurses to know what they’re doing fast because it saves lives,” she said. “And I know that goes without saying, in all places in the hospital, experience — you can’t put a price on it, and unfortunately it seems like they are. We feel so under-appreciated. We don’t feel respected, we don’t feel heard.”

For the former Intermountain nurse, she wants people to know that nurses become nurses to help people in their most vulnerable moments. She said the hospitals take advantage of the generosity, care and giving nature of their staff.

“When the hospital systems start taking advantage of their people, then it inevitably is going to create a crisis of care where we don’t have the tools or the ability to take care of our people and it’s going to show up in errors,” she said. “It’s going to be less safe for patients. And there’s no nurse in the world who wants to work in a situation where their patients aren’t safe, because it kills you to see that happen.”

What nurses are asking for is simple: take care of the people who take care of people. This includes retention bonuses, more paid time off, better maternity leave, comparable retirement packages to school of medicine employees, lower cost of benefits, respectful treatment and more.

According to the current U Health nurse, not only are nurses not treated like licensed professionals, but they are also not treated like humans.

“There’s just such an emphasis in healthcare and in this economy on productivity, but it does not acknowledge the humanity of the people practicing healthcare or those accessing it, quite frankly,” he said.

When the then Intermountain nurse was considering finding a new place of work, and was worried about leaving behind people she deeply cared for, her friend told her: “If you were to die tomorrow, your job would be posted before your obituary.”

U Health nurses were informed to await solutions from upper management on July 1.

Anonymity was granted due to fear of retaliation from employers.

Kaye Sharp • Jun 25, 2022 at 2:39 pm

I have been a Nurse for 25 Years and was a CNA/CHHA before that. It’s unfortunate for my Profession that not being able to urinate for a whole shift let alone eat is considered “Normal”. So is working one Nurse to 47 Patients with two CNA’s, who if I didn’t have I could NEVER have functioned. The State was called many times in different places and said it’s the Facility that gets to set the Safe Staff to Patient Ratio.

I had part of my Vacation time I had earned taken from me..as did the other employees…at one Facility to fund another Facility that “wasn’t doing well”. When we complained about it being Legal they said they had more Lawyers then we ever would.

This is not new. After the last Shortage that only turned around because the Economy collapsed, I think we are just OVER it. I am watching Nurses Early Retire or just Quite because they would rather do ANYTHING but this.

Nursing is a rotten place to be most days. We kill ourselves and this time were actually willing to die for our Patients and are LOSING our Jobs because we have valid reasons to not get a Vaccine..two years after this started…and are CDC Compliant.

YEP…the VA is getting rid of Nurses in a shortage..some that are Veterans…when we are already in a bind

That is how important we are

When the horror just started the VA alloted a 10 percent raise for Nurses…but not all Nurses got them at our VA. Other VAs did.

We are nothing but bodies to fill holes since time began. And it will NEVER change

Olivia Bohn • Jun 25, 2022 at 2:02 pm

I feel anxious just reading this post about the nurses. I am an RN with 40 years experience in multiple areas of nursing. I have bee ln left short staffed so many times and o that was before Covid. This is an issue that has never changed. Nurses are not made to feel important and are a dime a dozen. I still feel the same. A few years ago I decided it’s time to demand what I can do and not more. I work in home health and it’s the best. I pick and choose my patients and refuse to wear myself out. Should have done this 30 years ago.