The Art of Medicine

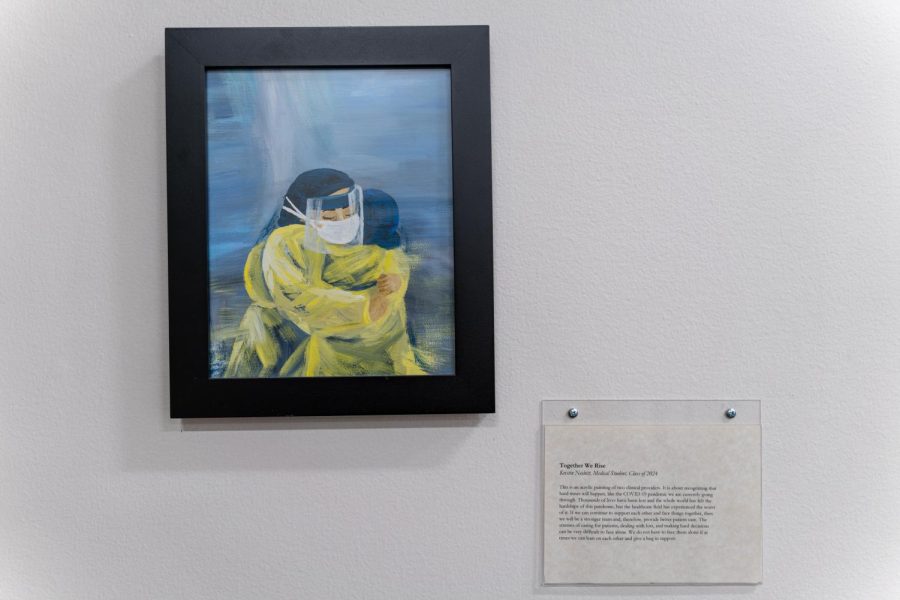

“Mutual Creation” by Tyler Kellis at Spencer S. Eccles Health Sciences Library in Salt Lake City, Utah, on July 6, 2022. (Photo by Xiangyao “Axe” Tang | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

August 28, 2022

Science versus the arts. Right brain versus the left brain. These two facets, faculties or skillsets always seem to be duking it out in a never-ending boxing match for superiority. This duel of fates is especially vicious in the realm of education. Institutions of learning constantly seem to value one above the other with no balance in sight. Obviously, there is at least some intersection between arts and science. A tattoo artist recently mentioned to me that their art would not be nearly as successful without their knowledge of color theory. A tenderhearted emergency room doctor recently held my wife and I’s hands and openly cried with us as they revealed devastating test results. The emotion found in art was improved by scientific study, while scientific results were made human by the vulnerability of these emotions.

Layers of Medicine

This particular intersection of art within medicine is especially fascinating to me. I have had the unique experiences of working for a medical school, having my partner work in a hospital and frequenting medical professionals due to health complications. Everywhere I look and breathe, the daunting field of medicine seems to be screaming at me.

In a recent experience, I was exposed to a series of art projects done by first-year medical students at the University of Utah School of Medicine. I learned that over the first two years of their education, medical students are required to complete an art project. The art projects completed are a part of the mandatory Layers of Medicine course which explores the complexities of a profession in the field of medicine and touches on the topics of culture, sex and gender, ethics, humanities and arts. The parameters of the art project are rather simple, as students are asked to interpret a topic presented in the course and translate this interpretation into an art piece.

‘If you call it art, it’s art’

I had the prestigious opportunity to sit down with the creators of this course, Gretchen Case, the director of the Center for Health Ethics, Arts and Humanities, and Karly Pippitt, a family medicine physician, to learn a little more about this art project.

Self-professed as two halves of the same brain, these two brilliant women bounced off of each other so seamlessly it was spooky.

After a brief introduction to their course, I dove right in with a question that had been digging to get out since I first saw the art projects. I had to know how they dealt with the almost obligatory eye-roll when their medical students learned they were required to create an art project. I have met enough medical students, both hopeful and current, to know how focused they are on the sciences. With a chuckle, both Pippitt and Case explained that, of course, they run into the Type A student who struggles to see the value in an art project, especially those at such a critical point in their education. There is also a common sort of anxiety from when students are required to create art. Being a medical student is extremely stressful and exhausting — to combat this, Pippitt and Case immediately emphasized that these medical students will not be graded on their artistic ability.

The purpose of the art project is not to create beautiful pieces that grab the attention of millions. Instead, the art project exists to allow students to think differently and to exercise a different part of their brain. The imperative part is that these students take the time to interpret the information in an artistic way.

“If you call it art, it’s art,” Pippitt said. “You just have to tell us why.”

Visual Thinking Strategies

Along with the emphasis on personal interpretation of information into art, the Layers of Medicine course also focuses on exposing students to art. Prior to the pandemic, medical students would often take a field trip to the Utah Museum of Fine Arts on campus.

“There is good data to say that engagement in the arts and humanities throughout training can be helpful not just with burnout, but with resiliency, wellness and even diagnostic and clinical skills,” Case said. “So, one of the activities we do with the medical students is called Visual Thinking Strategies.”

Visual Thinking Strategies is its own deeply engaging and well-researched barrel of monkeys. In part, it has to do with how each individual interprets visual images. Case and Pippitt broke it down into three essential questions. First, “What is going on in this image?” Second, “What do you see that makes you say that?” Third, “What else can we find?” These three questions, while simple, challenge students to train their brains into thinking about how they know what they think they know. It also pushes students to engage deeper with the art they are looking at. Instead of spending 20 seconds with a piece, they spend 20 minutes.

Case likened this exercise to a physician treating a constant slew of patients with pneumonia.

“If a clinician sees 50 pneumonias in a day, the 51st diagnosis may come as a habit — we want our students to really think about how they would know it’s a pneumonia, and how to catch if it is something else,” Case said.

Part of Being a Whole Person

The arts focus involved within the Layers of Medicine course works tirelessly to prove to students that art is not extra or tacked-on, unnecessary fluff. Art integration exists to help medical students become better doctors. However, something even more exquisite is at play here.

“We want students to engage with art because it enriches who they are as people,” Case said. “It is pleasurable, it is good to look at, it’s part of being a whole person.”

Case and Pippitt strive to remind their students that they are not just medical students or future doctors, they are humans who deserve joy, pleasure, visual stimuli and to form personal opinions.

The art projects turned in by medical students have ranged from a simple cup to a burned white coat. The importance lies in the interpretation of not just the student artist who created it, but also those who had the chance to view it. I could speak endlessly on the projects created and emotions elicited from this two-year mandatory, and clearly successful, medical school class.

A Range of Successes

Even with valiant efforts, some students simply won’t respond well to creating an art project. This does not mean they were not successful.

“Some students don’t enjoy the project and that’s fine,” Case said. “Sometimes a student will tell us that they didn’t enjoy the project, but they liked going to the museum. This is equally as important.”

At the end of the day, sometimes the only thing elicited from the art project is exposure to a new favorite art piece. Or maybe it’s just the personal knowledge that if they try, they can pull off an art project.

“Most people will appreciate art at some time in their life,” Case said.

Even if the appreciation doesn’t manifest itself during the art project, who knows what kindling has been laid to spark a fire later in life.

‘You can’t care about everything all the time’

One of the most important and fascinating things I gathered from this interview was the emphasis on art being a living and evolving discipline. Another golden nugget I treasured from Case: “you can’t care about everything all the time.” Obviously, we cannot care about everything all the time, and thus, most of our lives today might seem trivial in two years. The important factor is that we keep moving forward. Within Pippitt and Case’s discipline, the important thing they are trying to express is that art is worthy of being cared about at some point. It doesn’t need to be right now, but if the window is open, who knows what can reach us later in life.

Keeping a toe dipped in the ever-expanding ocean of the arts allows us as humans to express emotions, detoxify our minds and take a break from the busyness of life. If we keep coming back to art in any form, we give our lives the opportunity to be romanticized and beautified and our minds the opportunity to be expanded and edified. Clearly, there does not need to be a constant boxing match between arts and sciences. The truth is that whatever field we study, work and enjoy would benefit from a little more art in our science and a little more science in our art. This intersection will make us better not just as workers, but also as humans.

The art projects of U medical students can be found on the Instagram account @uusomlom as well as on display at the Health Sciences Library.