News x Arts: ‘Embodied Ecologies’ Explores Intersection Between Disability and Environmental Health

“c-x,” by artist and U student Chanté Burch, on display as part of the “Embodied Ecologies” art installation on the 4th floor of the Salt Lake City Public Library on Saturday, Oct. 22, 2022. (Photo by Jack Gambassi | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

January 1, 2023

“Embodied Ecologies,” a collaborative art exhibit consisting of work from 14 Utah-based artists, is on display at the Salt Lake City Public Library until Nov. 11. Its goal is to examine and explore the intersection between disability and environmental health, and centers artists with disabilities.

The project is “a collaboration between the Environmental Humanities graduate program at the University of Utah and local nonprofit Art Access,” said Natalie Slater, facilitator of the exhibit, in a written statement. “Art Access’ mission is to increase accessibility in the arts through programs for disabled artists and education for community and cultural institutions.”

Featured Works

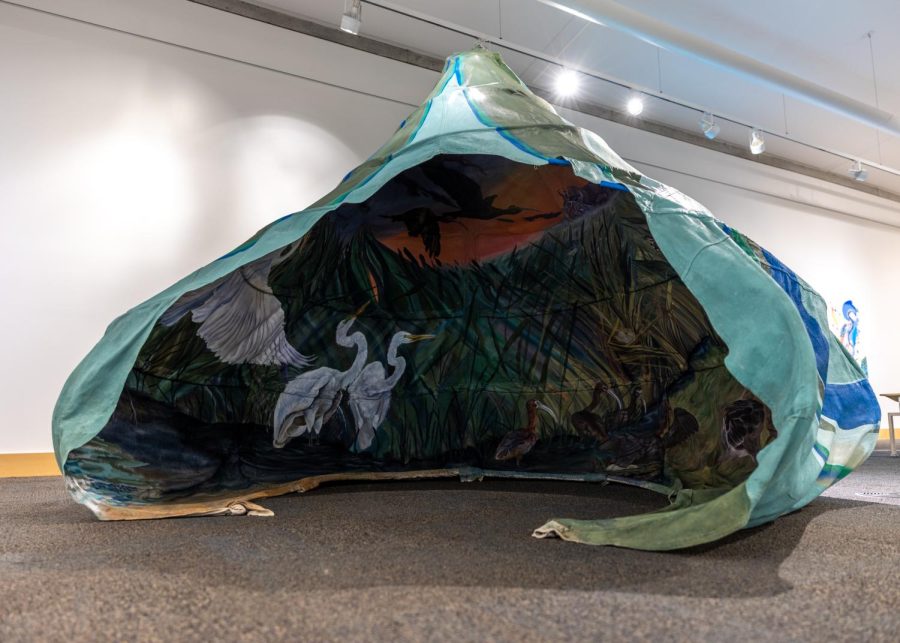

The largest piece on display for “Embodied Ecologies” is a yurt-like structure big enough for several people to sit inside called “What Happens in the Marsh at Dusk” by Evangaline Amadu. Even though it’s the largest piece on display, it’s made from the rather simple components of PVC pipe, acrylic paint and canvas. Inside, viewers are enveloped in a quiet, peaceful point-of-view style scene of wildlife amongst the dark green reeds.

A few finches gather to the left, pint-sized chicks wander around an egg-filled nest near the middle and pelicans bustle about on the left. A gray lynx is almost invisible crouching in the distance on a gray rock, staring hungrily at the birds ahead. Above, geese fly in formation against the sky painted in hues of red and orange by the setting sun. It’s a peaceful but active scene full of vibrancy in the chosen colors, and life with the depiction of wildlife.

“I hope it brings a little cheer and wonder to your day,” Amadu wrote in the artist’s statement. “I hope it helps remind you that you’re a part of a big wild world that’s itching for you to know it.”

Another piece featured in the installation is “Chair No. 2” by Laurie Larson which takes the form of a white blob that looks like coral skeletons or fungi held together by wood. Simply made from maple and upholstery, the piece has the profile of a chair but functionally looks more like the suggestion of a chair.

The piece is an anti-love letter to a bright green plastic chair Larson used to own. In her artist statement, she describes it as “designed to visually echo bodies; looking all at once to be dendriform, animal-like, and fungal.”

A Disabled Environment

Stan Clawson, an independent filmmaker and adjunct film instructor at Salt Lake Community College, worked with Natalie Slater to create a short film displayed in the exhibit, also titled “Embodied Ecologies.” It includes footage of all of the other artists working on their pieces.

“The fact that there’s this pairing of art, environment, which I’m very interested in, and also disability, I think that was just this great sort of pairing that really captivated me and made me interested in this project,” Clawson said.

As the documentarian on the project, Clawson was able to sit in on the artists’ creative processes and attend meetings where the artists showed and discussed their works with each other.

Clawson, who uses a wheelchair, said that those with disabilities are hyper-aware of the way they are connected to the environment, and he was excited to have the opportunity to explore that further through art.

“I’m already very aware of these landscapes that we continually create that are for non-disabled individuals,” he said. “As I got on this project, I started to rethink the environment and landscapes in different ways. What happens if the environment becomes disabled?”

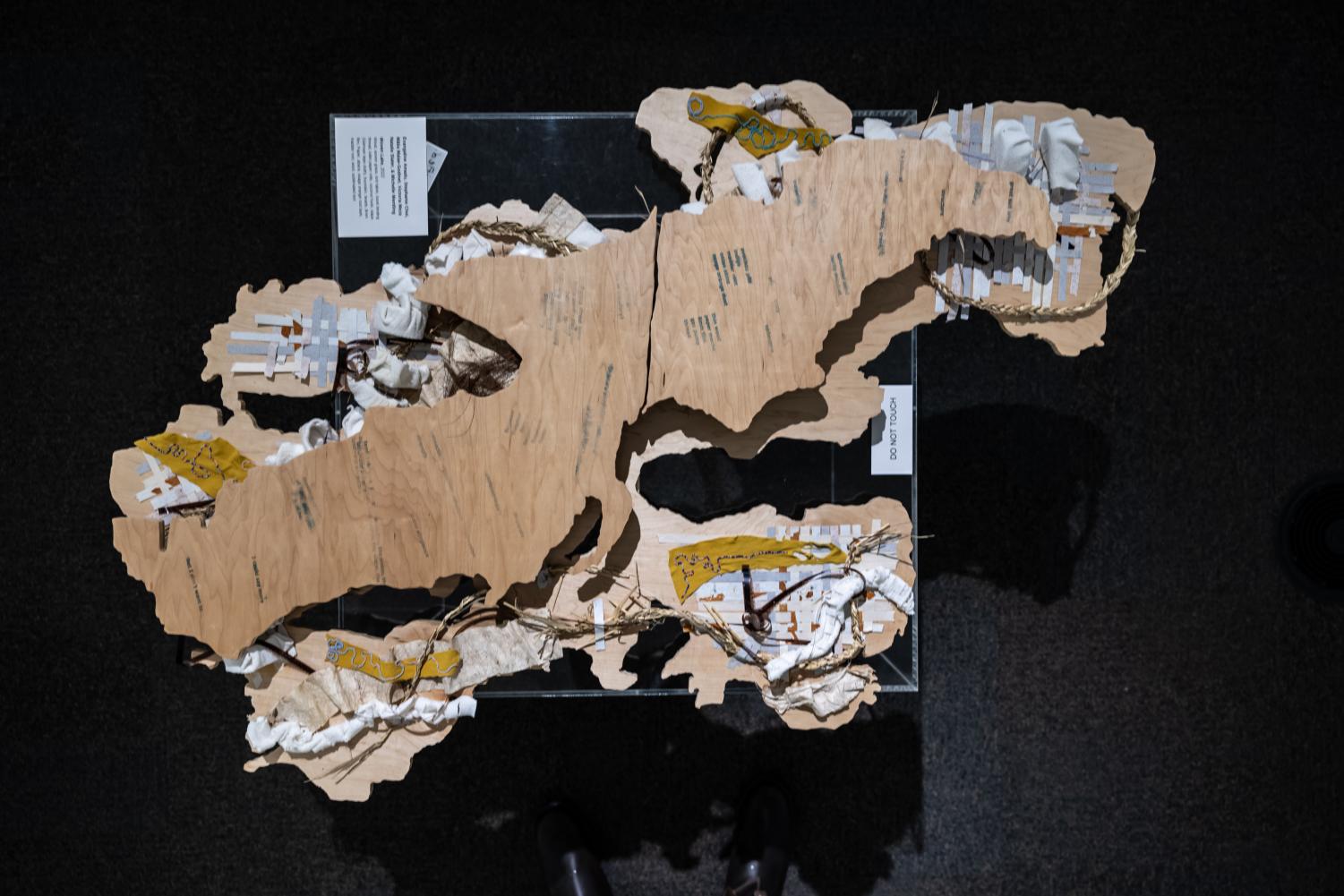

He cited the shrinking of the Great Salt Lake as one of these environmental disabilities, which is an issue discussed by “Woven Lake,” a collaborative art piece in the exhibit by Amadu, Stephanie Choi, Mālia Malae-Godinet, Victoria Meza, Natalie Slater and Michelle Wentling.

The piece is made from over a dozen different materials including both natural and synthetic, such as osage orange root bark, toilet paper rolls and siapo, a kind of Sāmoan tapa cloth. The piece rests on a low table under lights so that any viewer may look at it from above.

Many Utahns would be able to recognize the lower half as the outline of the Great Salt Lake but probably not the shape of what the lake currently looks like. It is plain and small, with barely legible text across it. Between the two are the piece’s other materials: a long strand of woven grass, roots poking out from underneath, and smatterings of beads on string glued to yellow fabric. It’s as if these materials, symbolic to Utah, are trying to bridge the gap between the lake as it used to be and as it is now.

“To have a striking image of the current shape of the Great Salt Lake hovering over an older, sort of full, healthy shape of the Great Salt Lake, that’s a pretty striking juxtaposition,” Clawson said.

The light shining casts a shadow over the lower half.

“I just kept looking at the shadow and thinking, ‘Wow, how should we interpret this shadow of this thing that is our namesake and what are we going to do about it?’” Clawson said.

KSL News reports that the Great Salt Lake has shrunk to nearly half of its volume and now 800 square miles of dried lakebed are exposed to winds that will spread toxic clouds of dust across the Wasatch Front. This piece acts as a visual reminder of how much the lake has shrunk over time.

Addressing the Environment with Art

Douglas Tolman, a graduate student at the University of Utah studying sculpture, who was not a part of the exhibit, said that when it comes to environmental art, such as that displayed in “Embodied Ecologies,” there are two main approaches.

“One is a more or less didactic form of art that leads you to a point and leads you to a conclusion that the artist wants to lead you to,” Tolman said. The other approach “revolves more around an inward-out approach, which is asking questions so that viewers and participants can kind of come to their own conclusions about how they feel about things.”

He added that environmental art in general is shifting more towards the latter approach.

“I think you used to see really big pictures of smokestacks pouring out fumes and you’d see really nice photographs of polar bears on ice caps and sculptures of oil dripping over globes and things like that,” Tolman said.

He explained that that type of art, which aims to shock viewers, has become less popular because most people have already made up their minds about climate change. Instead, artists are now attempting to open a conversation, ask questions and compare viewpoints.

“I think that that’s really where it is in regards to climate change right now,” he said. “Art has the ability to open questions, not to close dialogue.”

Disaster and Disability

Another way that the environment may become disabled, Clawson said, is through disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which affects humans with disabilities disproportionately, according to the National Governors Association.

“That was a big part of the COVID story and this idea of what happens if unhealthy viruses or contaminants or environmental factors begin to envelop a community and who is most at risk, and oftentimes, it’s those individuals who have disabilities,” Clawson said.

This connection is exactly what is examined in “c-x,” by artist and U student Chanté Burch.

As an abstract piece made from plaster, metal and concrete, the piece includes stark-white hands carefully caressing a metal disc on a raised dais, just barely skimming the surface of it. The disc is coated in many smears from the hands and surrounded by broken fingers. In the artist’s statement, Burch describes their motivation behind the piece as being inspired by the pandemic and the sudden obsession with cleanliness. They point out the negative environmental consequences of increased production and usage of strong antimicrobial chemicals.

With this in mind, the broken fingers carry a new meaning. Perhaps the disc is not being contaminated by the plaster hands but sanding them down bit by bit until they break off like the surrounding crumbled fingers.

This, Clawson said, is exactly the importance of looking at these issues through art because it allows the viewer to examine them from an entirely new perspective, even just based on the physical location, or a short paragraph about the artwork.

“That’s what I love about art, is it lets you see something in a way that maybe you haven’t thought about or it puts it into a context where suddenly you’re like, ‘oh, wow, there it is,’” he said.

This is the goal of “Embodied Ecologies” — not to preach to or shock people, but to raise questions and re-contextualize the issues of disability and climate change. This is why Clawson was so excited about coming on board for it because it challenges viewers to think about issues that society does not generally like to think about.

“We still live in a society where disability is very invisible, right?” he said. “Disability is often thought of as an acknowledgment sometimes of how vulnerable we are, and how mortal we are, and I think it’s so interesting when I think about something like the Great Salt Lake or our environment and how a lot of times we don’t want to talk about what’s happening in our environment just as we don’t want to tackle what’s happening with disability.”

This article was updated on Jan. 4, 2023, to clarify/correct the following:

The “Embodied Ecologies” exhibit doesn’t just feature several artists with disabilities but rather centers disabled artists.

The film displayed in the exhibit was not a documentary but rather a short film created by Natalie Slater and Stan Clawson. The documentary is a separate project by the two that is still in the works.

Artist featured in the exhibit is Mālia Malae-Godinet not Mālie Malae-Godinet.

The exhibit is a collaboration between the Environmental Humanities graduate program at the University of Utah and local nonprofit Art Access.

The article was restructured to more accurately reflect Douglas Tolman’s role in the piece. Tolman was not involved in the “Embodied Ecologies” exhibit.