U Class Centers Community Voices on Housing Issues as Displacement Worsens

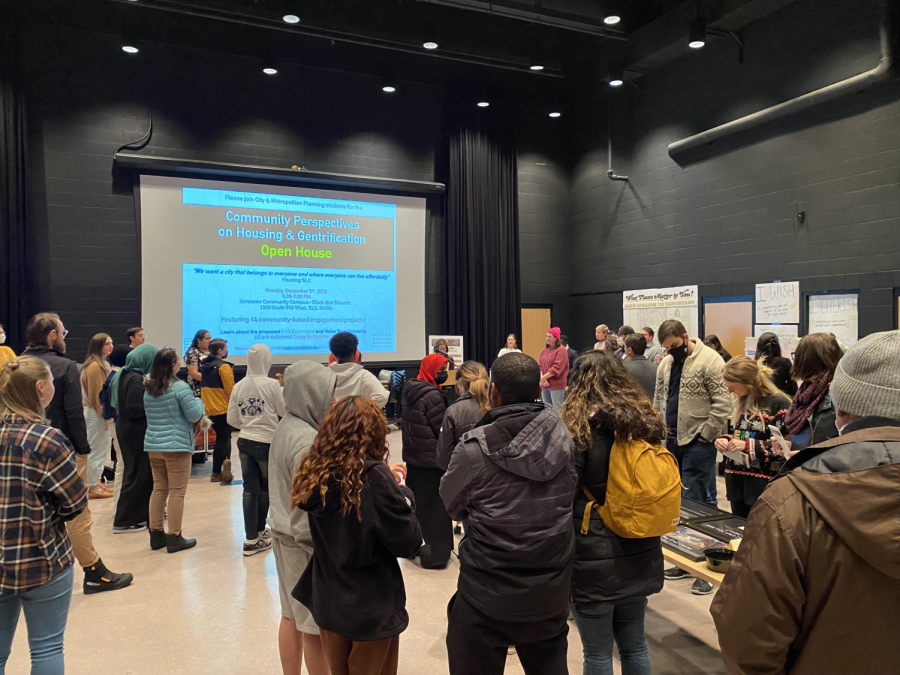

Students in the City and Metropolitan Planning Department present their community engagement projects on Dec. 5, 2022. (Photo courtesy of Caitlin Cahill)

March 9, 2023

Displacement in Salt Lake City is getting worse, and disproportionately impacting communities of color, according to Thriving In Place, a community anti-displacement strategy overseen by the Salt Lake City Department of Community and Neighborhoods.

“Some of the findings from that summary report was that displacement in Salt Lake City is significant … it’s getting worse, there’s a lot of concern about it,” said Caitlin Cahill, a professor who taught a community engagement class in the graduate program for the University of Utah’s City and Metropolitan Planning Department in Fall 2022. “This was something that the Urban Displacement Project has not seen before in their work around the country, is that there are no more affordable neighborhoods in Salt Lake City, where lower-income families can move once they’re displaced.”

The class Cahill taught was informed by the anti-displacement framework created by Thriving In Place.

“I think something that’s really important for the work that’s being done on the West Side communities is that the patterns of displacement reflect the historic patterns of discrimination and segregation,” she said. “So those areas that experience high [displacement] were those areas that were redlined in the past.”

The class was a partnership with Housing SLC, the city’s new housing plan centered on affordability, which is set to be adopted by June 30, 2023. Cahill explained the class intended to enrich the city’s community engagement.

“This was also like trying to reach out to folks who are not often engaged with,” Cahill said. “And so that’s a larger context. So unsheltered folks, folks who are living on the West Side, folks of color, queer folks, I mean, there’s not usually specific engagement.”

Cahill said policy work can often be “extractive.”

“The very communities that are often getting the most studied do not often get a sense of how their participation actually affected the policy, or in this case, the Housing SLC plan,” she said.

This directly influenced how Cahill structured her class — students partnered with different community organizations and completed projects that determined appropriate outcomes for how their engagement could be used by the community partner.

This model was informed by the University Neighborhood Partners’ guidelines on community-based research including shared goals and values, community strengths, equitable collaboration, collective benefit, trusting relationships and accessible results.

“It isn’t just kind of like an intercept interview on the street, but actually a way to really center the concerns and priorities of those who are most affected by the issues,” she said.

Mapping Stories

Lucas Horns and Jeresun Atkin, two students in the U’s city and metropolitan planning graduate program, partnered with the Nuanua Collective, a “social support group for LGBTQ+ Pacific Islanders,” as described on their instagram. Together, they created focus groups to discuss housing issues.

From their first conversation with members of the Nuanua Collective, they saw the reality of queer geography.

“Queer communities are being shaped, for sure, by rising housing costs,” Horns said. “It’s not that queer communities necessarily are being displaced or disenfranchised, but they’re becoming more white. And so queer people of color are kind of the ones facing this kind of unique burden when it comes to gentrification.”

The focus group documented spaces that felt LGBTQIA+ and racially inclusive. They then made a story map to visually respond to the question: “How is gentrification affecting the geographies of race and queerness in the Salt Lake region?”

Horns said overlaying different maps was helpful to visualize trends of dispersal.

“The concentrations that are in the urban core in kind of these like more liberal, more affluent neighborhoods near Salt Lake City, the queer populations kind of doubled down and became more concentrated, but those are the same neighborhoods that also became more white,” Horns said.

The project reports, “The majority of LGBTQIA+ inclusive establishments identified during the mapping activity were located in Salt Lake City. However, many of those within Salt Lake City – [particularly] those in the urban core – were not identified as racially inclusive,”

They further looked into census data, analyzing demographic changes in the last decade. They found as LGBTQIA+ individuals concentrated in the urban core of Salt Lake City, people of color were displaced to surrounding areas, where it is less safe for them to be queer and a person of color, according to Jakey Siolo, the director of the Nuanua Collective.

“We showed some voting data showing that these districts where they’re moving to are represented by legislators who vote on … anti-trans and anti-queer legislation,” Horns said.

According to Horns, as the city becomes less affordable, it also becomes less diverse.

“As costs go up, as we found in our project, you know, the city is losing its diversity of culture and gender that makes it appealing in the first place,” Horns said.

Atkin said from a planning perspective, understanding how to engage with different communities is crucial to inclusivity.

“And ensure that planning practices are creating better urban areas for everyone and not just excluding some along the way for the profit of like, better luxury apartments or bigger chain business establishments that do prevent people from experiencing that inclusivity that everyone does deserve in an urban area,” Atkin said.

The Meaning of Home

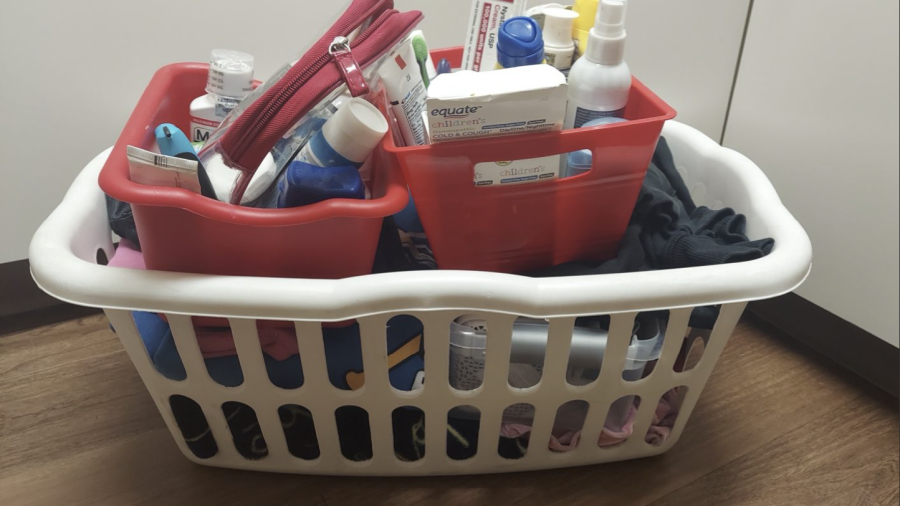

Partnering with The Road Home, an organization that assists people experiencing homelessness, Kaden Coil, a master’s student in public administration at the U, created a photo voice project allowing unsheltered individuals to share their stories. Coil and the organization noticed in the summer and early fall that a lot of the families who were seeking shelter were being turned away from shelters because capacity had been met.

“We saw a lot of people staying in their cars or in places not meant for human habitation,” Coil said. “So when that happens, a lot of families tend to stay in the shadows to avoid contact with [police] or DCFS in fear of like, having their kids removed and a lot of societal stigmas and judgment. So we don’t really know their needs. We don’t know their stories.”

After noticing this, they started to ask participants to take photos of what home means to them and what they’d want the city and community to know, which allowed people experiencing homelessness to “control windows into their life,” Coil explained.

One photo entitled “The End Game,” depicted a child sitting on a bed, across from a dog.

“When someone is hospitable enough to offer you shelter-repay them with good deeds. … Use the sleepless nights to find a way out of this mess. … Expect failure, a win or two–more failure; just don’t lose sight of the end game,” the description read.

They also created 15 rules for navigating homelessness. The first rule: minimize.

“When you get the heads up you’ll no longer have a home- sell whatever you can that isn’t important- throw away the rest,” the brochure read.

Coil explained the visual component of this project was about control.

“There’s a lot of stigmas or a lot of stereotypes about people experiencing homelessness, especially families, so allowing them kind of to control and show … this is my life in this moment, we found that to be most impactful,” Coil said. “And it’s more an element of control for them rather than having to engage in and be at the whim of somebody else. They have the control of what they’re showing.”

The project was both about home and the systemic factors perpetuating homelessness.

“I think the largest finding we found was the cliff effect of our social service network,” Coil said. “So as families are encouraged to do better for themselves, then we start to remove this social safety network, so we cut back their food stamps, we make them pay their insurance, and we take away their childcare which only contributes to this cycle and they were right back to where they are.”

Another finding was that access to reliable transportation “is the lifeblood of an unsheltered family,” Coil explained.

With Salt Lake City residents becoming increasingly rent-burdened, Coil said more people are at risk of becoming homeless.

“Homelessness affects all populations — it doesn’t discriminate,” Coil said. “And it is more common than you’d ever imagine.”

Coil explained this project was crucial for improving public administration specifically.

“When we are dealing with nonprofits and we’re providing goods and services that are issued from the government, we are dealing with the most vulnerable at times and marginalized and so having an understanding of their experiences, knowing their stories and their voice, being exposed and educating ourselves is vital if we are to continue to provide those goods and services in a better fashion,” Coil said.

Cahill explained the partnerships between the students and their respective community organizations were powerful collaborations, mentioning the significance of the trust the community partners placed in the students to do meaningful work.

She’s also grateful for the students.

“It’s not always easy work,” she said. “But these projects, they really understood what it meant to collaborate, and what equitable collaboration looks like and how to foreground the strengths and the assets of the community.”