Shrinking Great Salt Lake is a ‘Solvable problem’

Participants at Rally To Save Our Great Salt Lake at Utah State Capitol in Salt Lake City on Saturday, Jan. 14, 2022. (Photo by Xiangyao “Axe” Tang | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

April 18, 2023

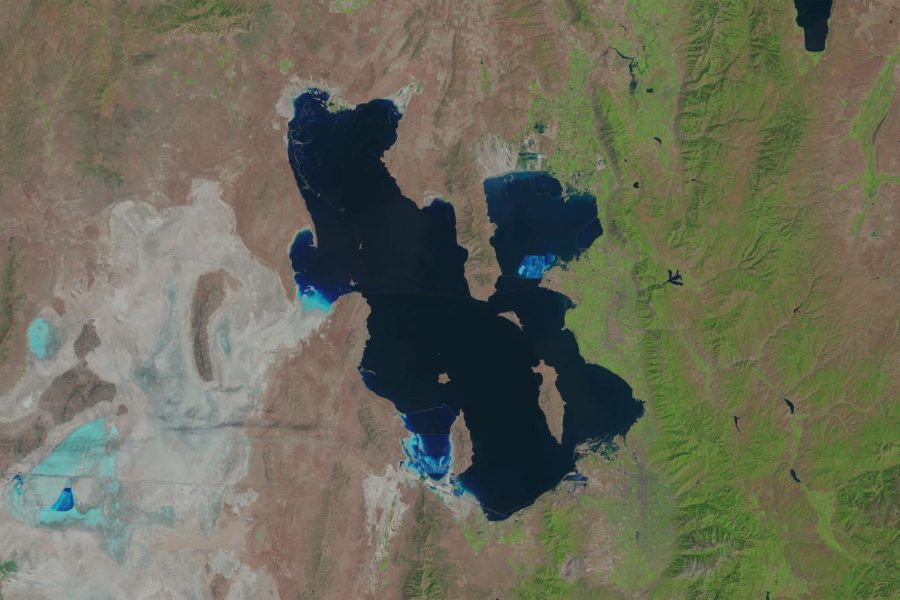

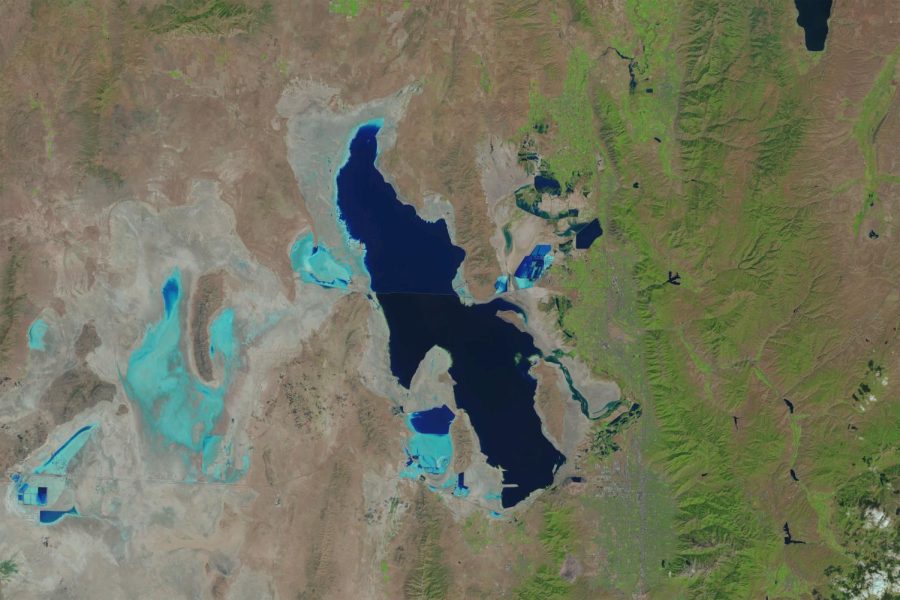

The Great Salt Lake is projected to disappear in five years, a new BYU study shows. In November 2022, the lake dropped to a new record low elevation of 4,188.5 feet, according to KSL News Radio.

The lake levels have risen due to recent snow storms but community members and experts are calling for wide-scale and long-term changes — the solution to increasing the lake’s water levels is not simply about waiting for rain.

Being a FRIEND of the Lake

Katie Newburn is the education and outreach director for FRIENDS of Great Salt Lake, a membership-based non-profit whose mission is to “preserve and protect the Great Salt Lake ecosystem through education, research, advocacy and the arts,” according to Newburn.

FRIENDS was founded in 1994, in response to declining lake levels caused by water diversion and overconsumption upstream, which “account for about 11 feet of the lake’s decline below its healthy average level,” Newburn said.

FRIENDS advocates for water conservation upstream of the lake, “by all varieties of water users,” Newburn said. The organization is concerned about the vulnerability of the lake’s ecosystem.

“As the lake is getting smaller and lower, it’s also getting saltier, which represents, I would say, the most imminent threat to the lake’s ecosystem functionality of the food web within the lake, which includes bacteria, archaea, algae, which is consumed by brine shrimp and brine fly larvae in the lake,” she said.

Birds are also an integral component of the lake’s ecosystem — when they cross Utah on their migratory paths, they rely on brine shrimp and brine flies for food.

According to Newburn, the lake is not only an economic value to the state but also improves the quality of life within Utah, as a “natural form of dust mitigation.” As more of the lakebed becomes exposed, more toxic dust is released, disproportionately impacting West Side communities.

‘Just add water’

The solution seems simple — just add water. Newburn said this is easier said than done, especially in Utah, where a finite water supply is already allocated.

“And really, it comes down to every type of water user needing to do their part to use less,” she said.

Newburn explained in the Great Salt Lake watershed, the majority of water is allocated to agriculture.

“One focus that the state has already been working toward is what they call agricultural water optimization, basically subsidizing new or better irrigation technology so that farmers can grow the same yields of crops using less water and allow the difference to go to support the lake,” she said.

Gabriel Lozada, an associate professor of economics at the University of Utah, has been researching Utah water problems since the late 1990s. He said the solution to the shrinking Great Salt Lake is simple: stop diverting water for agricultural use.

“What we actually have to do is to stop interfering with the natural flow of, let’s say, the Bear River or the Weber River,” he said.

He posed the question: if agricultural processes are affected, would farmers be compensated for the loss of their crops?

“If so, how much do you want to reimburse people whose livelihoods depend on farming but aren’t farmers themselves?” he said.

This session, the governor’s budget allocated $200 million to agricultural water optimization. Some, but not enough action was taken to save the lake, according to Courthouse News Service.

Newburn also hopes municipalities will adopt measures to achieve municipal industrial water conservation.

“Utah is the fastest growing state in the nation — it’s essential that how we grow is in a water-efficient manner and in a manner that is effectively planning for the water demands of the future,” she said.

Newburn said it is encouraging that the lake has risen slightly due to the deep snowpack this year. The caveat: there is no guarantee all this water will reach the lake.

“Where it will go first is to all of our reservoirs, which are generally quite low below their average capacity,” Newburn said. “It’ll be up to our state agency leaders and some of the leaders in the major water districts in Northern Utah to decide if and how some of that snowpack water storage will be released to the lake, if any at all.”

Six Recommendations

Paul Brooks, professor of geology and geophysics and director of the interdisciplinary graduate hydrology program at the U, was part of a strike team geared at providing impartial, solution-oriented, peer-reviewed information on what is and isn’t possible in regards to the Great Salt Lake.

The strike team consisted of experts from the U, Utah State University and various state agencies. They outlined six recommendations for state leaders.

“There wasn’t any agenda to it, it was as impartial as we possibly could be in evaluating all the possibilities and the threats that are for the future,” Brooks said. “We need all hands on deck.”

Brooks said the lake responds naturally to climate variability — meaning it goes through wet and dry cycles — but overconsumption of this precipitation is driving the decline of the lake level.

“So the problem is largely us,” he said. “Natural climate variability has reduced the lake level 10% or less. And over two-thirds of the decline in the lake has been driven by our consumptive uses.”

The first recommendation — leveraging the wet years — means not thinking the problem is over when a wet year comes around.

“So take advantage of those years to get as much water to the lake as possible,” Brooks said. “Don’t think that because it’s wet now is not the time to conserve or that we can put it off for a year.”

Brooks said the second recommendation — setting a lake elevation range goal — is important for making a narrative about the value of the lake into a tangible target. A resolution to set a target elevation goal was struck down in a Senate committee hearing on Feb. 1, 2023.

“It’s hard to evaluate our progress if we just have a narrative,” he said. “If we put a range goal on there, we can say this level will avoid the collapse of brine shrimp, this level will have this much of an improvement effect on human health and so we can track our progress and it’s easier to make progress if you track it.”

Conservation, the next recommendation, is essential for getting the lake back to a healthy level, Brooks explained.

“It’s going to take a little bit of resources, and by investing real dollars in conservation, we can have a major impact on the lake level, because that’s really our only policy level, is being more efficient with water,” he said.

Lozada acknowledged that while the amount of water people used in the 20th century may have made sense, it no longer does because of climate change.

“We have to make choices,” he said. “They’re not choices between valuable things and non-valuable things. They’re not choices between being wasteful and being wise. They’re choices between valuable uses of water. They’re all valuable. So then we have to ask, ‘Well, which ones are more valuable?’”

In regards to water monitoring and modeling, the next recommendation, Brooks said Utah’s current records are pretty good, but “relatively coarse.”

“What are the biggest users, the smallest users?” he said. “What are the ways in which we can get the most bang for our buck in terms of conservation? So we need that data.”

This data would aid in developing a holistic water management plan — the second-to-last recommendation. Brooks explained that water is managed annually, but the lake “responds on a multi-year timescale.” So, it’s important to think more long-term and comprehensively about water use.

“We need to bring together all the different users, all the different utilities, all the different folks that are involved in measuring, monitoring, predicting and delivering water resources to all of our downstream users together into a comprehensive plan so that everyone is working towards a similar direction,” Brooks said.

Finally, the strike team recommended that the legislature conduct an in-depth analysis of policy options.

“The strike team welcomes and encourages the legislature, the governor’s office, to use its expertise when ideas come through,” he said.

Brooks urged state leaders to consider the recommendations of the expert team.

Pieces of the Puzzle

With something as fundamental as water, Brooks acknowledged people might be reluctant to change their ways.

“We’re not asking folks to give up anything,” he said. “We want everyone to have the same quality of life and the business and the agricultural opportunities, the recreation opportunities that they’ve had in the past. But I think there’s always a little bit of concern when you’re asking folks to change how we want to conserve.”

This is why investment from government agencies, in addition to small changes by the general public, is the solution, Brooks explained. He said each of these recommendations can not work individually.

“All six of these should be a piece of [the] puzzle to help people realize that no one has a target on their back here,” he said. “And if everyone pulls together, we can save the Great Salt Lake at a level that brings us all our benefits and still have a life that’s pretty similar to what we have now.”

While Brooks said society can’t continue to do things the way they have in the past, he emphasized that this is a solvable problem.

“I think the overall message is this is an optimistic report,” he said. “It is doable. It will be challenging, but it’s not terribly difficult.”