Jarvis: Queerness Isn’t Vulgar

(Design by Claire Peterson | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

June 22, 2023

My parents’ Netflix account has content restrictions on anything rated higher than PG-13 due to their personal beliefs, and I’ve used it for years. When Netflix forced us to make separate accounts, I immediately noticed how much more LGBTQ+ content was available, thus out of reach for many kids and teens. Queer content is held to higher rating standards than other content, often viewed as inappropriate for children.

Claiming that queerness is vulgar is an easy way to frame homophobia as protecting children, but restricting access to LGBTQ+ content harms queer youth. Representation in the form of TV, books and curricula provides familiarity so queer people can explore and learn about their identities safely.

Fear of the Queer Child

“There is enormous power in getting to frame an issue,” wrote researchers O’Loughlin et al. Last September, protesters at a family-friendly drag show in Provo called performers and LGBTQ+ students pedophiles and groomers.

This isn’t a new concept — the moral panic around queer people is “thousands of years old,” wrote Clifford Rosky in “Fear of the Queer Child.” People like these protesters believe that exposure to LGBTQ+ people will make the children in their families and communities queer, as if they could catch it like a cold.

When they frame queerness as obscene, it follows that queerness poses an inherent threat to children. It also reinforces the idea that being cisgender and straight is the norm — that it’s safer and more acceptable.

I spoke to Rosky, who’s also a professor at the University of Utah. This fear of queer children “devastates queer youth,” he said. “It is premised on the belief that they don’t exist and should not exist and should be prevented from existing.”

These beliefs lead parents, lawmakers and school administrators to restrict LGBTQ+ content in the name of protecting kids. They ban books. They complain about kids’ cartoons with LGBTQ+ characters, and they inhibit queer inclusion in classrooms.

Queer Erasure

MPAA ratings make it difficult for queer children and teens to find representation on television. Even if this erasure is unintentional, prioritizing queer media over heteronormative media would ensure a balance of mature and child-friendly LGBTQ+ content.

If youth can’t access queer TV shows and movies, they should at least be able to read queer books. But the majority of books that are challenged in school districts contain LGBTQ+ themes. In Utah’s biggest school district, several titles were pulled off the shelves last year. The parents who complain justify this by claiming gender fluidity and dysphoria are mental illnesses and deem LGBTQ+ content as pornographic. Through book bans, they attempt to erase queer people and their experiences.

Sometimes this erasure is more explicit. Florida’s H.B. 1557 restricts discussions of gender identity and sexual orientation in classrooms. Utah proposed a similar “Don’t Say Gay” bill this year, which was amended with improvements. But book bans reach the same goal if teachers don’t have these critical conversations with children. Worse, Gov. Spencer Cox banned gender-affirming and life-saving health care for transgender youth, furthering the narrative that queerness is inherently bad and must be contained — that queer people shouldn’t exist.

“When you’re hearing that from judges and from politicians and from certain — not all, but certain — religious leaders, and then you look at the TV and you don’t see yourself, that’s like a kind of implicit endorsement of this fear [of the queer child],” Rosky said.

Representation Protects Youth

Protecting youth involves providing safe spaces for them to learn about and discuss their identities, like seeing themselves represented in cartoons and other forms of media. Otherwise, they may explore their identities in dangerous ways, like on Grindr or in relationships with older people.

Rosky emphasized, “It is a matter of great importance, perhaps survival, for LGBT youth to see themselves in others, just like all people. We all need someone to look up to.”

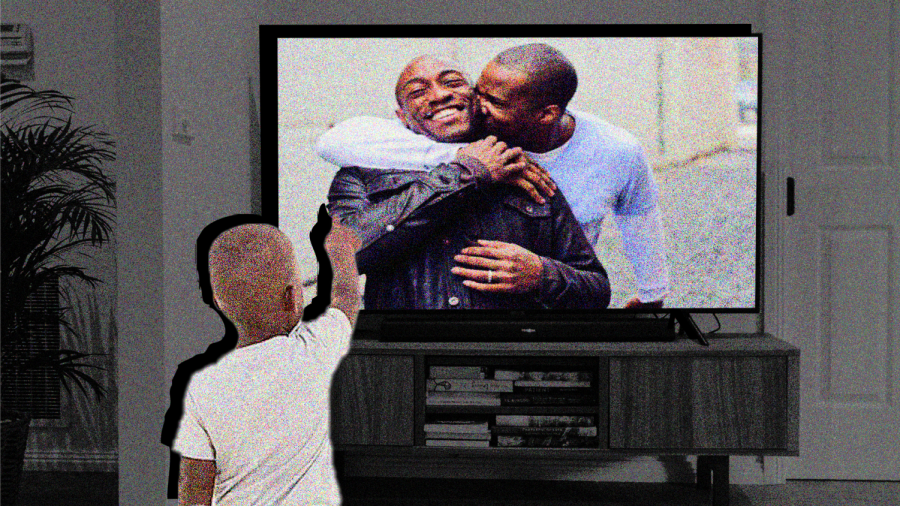

Seeing oneself represented on TV can provide coping mechanisms and community, as well as increase resilience against bullying. Familiarity also reduces prejudice and stigma, so seeing queer people on television can increase acceptance of them.

There is a long way to go — white gay men are still the most represented LGBTQ+ people in films. We need more queer people of color accurately represented in the media, especially trans and nonbinary people. We need to see more happy queer relationships and varied queer experiences. And children need to see other queer children on TV.

“Possibilities,” wrote actor Elliot Page in “Pageboy,” his recent memoir. “That sense of possibility is one of the main components of life lost when we lack representation: options erased from the imagination, narratives indoctrinated that we spend an eternity attempting to break. The unraveling is painful, but it leads you to you.”

Pretending that queer people don’t exist doesn’t make us go away — it only causes harm. Not having access to LGBTQ+ representation made it difficult for me to understand or feel comfortable with my own queer identity as a kid. I believed the lies told by people who were afraid and wanted to keep us silent. Watching queer television and reading queer literature as an adult has been healing.