Gholami: White on Paper, Brown in Public: Issues with the Census Race Question

ASUU and the Hinckley Institute are collaborating to encourage all students to fill out the census. (Courtesy of the Hinckley Institute)

June 1, 2020

The Census is a colossal undertaking with high stakes, the implications of which will shape the lives of Americans for years to come. Census numbers inform decisions about how federal money is allocated to public infrastructure like hospitals, schools and transportation in addition to determining congressional seats and voting district boundaries. Ensuring that the Census is both representative of, and accurate to, the communities surveyed is critical because data inaccuracies can result in long-term negative consequences — so it matters not only what the survey asks, but how.

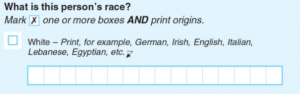

The origins of the Census Bureau’s wording of the race question is rooted in America’s history of racial discrimination. The first U.S. Census viewed citizenship as a proxy for race by sorting people into three categories: “free white males [and] females,” “all other free persons,” and “slaves.” The race classification questions on the Census have been shaped largely by white statisticians and lawmakers who were keen on identifying the white percentage of the American public as a measure of national purity. Presently, on the 2020 Census, not only are persons of European descent obliged to mark “white” on the census, but those of Middle Eastern and North African descent are as well. According to the Census, people from countries like Ireland, Egypt, Germany and Afghanistan are all considered to be white. If people of Middle Eastern and North African descent are not treated as white at TSA checkpoints or science fairs, then why should they be classified as such on the nation’s biggest data set?

As recently as 1952, whiteness was considered a prerequisite for citizenship and Christianity was held as a symbol of white identity. Arab immigrants who could prove they were Christian had a far better chance of attaining citizenship in the U.S. than those who were Muslim. Judges at the time mistakenly conflated Arab and Muslim identity, which resulted in many denied citizenship applications. Now, while people of MENA descent are white according to the Census and other racial categorization questionnaires, they are treated as anything but white in other spaces. This community is subjected to multiple forms of discrimination and daily prejudice that people of European origin do not experience in the United States. A 2015 study on housing discrimination found that young women with Arab-sounding names who posted ads for roommates received 40 percent fewer replies than those of young women with Anglo-European names. A similar study on employment for managerial positions found that resumes which listed Arab-sounding names received half as many responses as resumes with identical qualifications and white names. Two Palestinian men were stopped from boarding their Chicago flight when someone overheard them speaking Arabic and reported feeling unsafe to fly with them. In Oklahoma, a Christian Lebanese man was murdered by his neighbor because he was perceived to be a Muslim. These occurrences illustrate that despite being classified as white, people of MENA descent have fundamentally different experiences of American liberty.

Arab-Americans have lobbied since the 1980s to change institutional and governmental race classification questions in an attempt for the government to recognize the unique elements of Arab life in the United States. When presented with the option of a MENA category on the Census Bureau’s 2015 National Content Test, an overwhelming majority of respondents with Middle Eastern ancestry chose to identify as such. The MENA category would have served as an important clarifying update to the race question on this year’s survey, but persons who write in “Middle Eastern” or “Iranian” will continue to be treated as having mislabeled their responses and are instead recorded as “White.” The challenges of people with heritage from MENA countries are drastically different from those of white people in this country and inaccuracies in demographic data only serve to erase those discrepancies.

The authors of a 2017 study found that Hispanics, Latinos, Middle Easterners and North Africans tend to be undercounted on the Census and the consequences of their misrepresentation affect federal policy as well as program funding for these communities. For example, forcing MENA people to identify themselves as “some other race” presents huge issues. According to a Chronicle article from last year, the results of the 2010 Census cited “some other race” as the third largest racial group. An L.A. Times analysis of Census Bureau data found that there are roughly 3 million people living in the United States who are of Southwest Asian, Middle Eastern or North African descent. When minority communities are undercounted, areas in the United States with large MENA populations receive neither adequate nor proportionate funding for schools, hospitals and other critical infrastructure to address their unique needs, further perpetuating their marginalized position within American society.

Until the MENA community is granted its own box on the Census, they will continue to be functionally invisible to the government. It is this invisibility that leads to being under-recognized and thus underserved by policy makers, advocacy groups, social scientists and others who work to address the specific needs of their communities. Throughout American history, the recognition of whiteness for many immigrants has signaled their long-awaited inclusion into broader American society, but in case of MENA individuals, it is their “whiteness” that prevents them from becoming so.