‘Summer of Soul’ Records a Forgotten Festival and Celebrates a Revolutionary Era

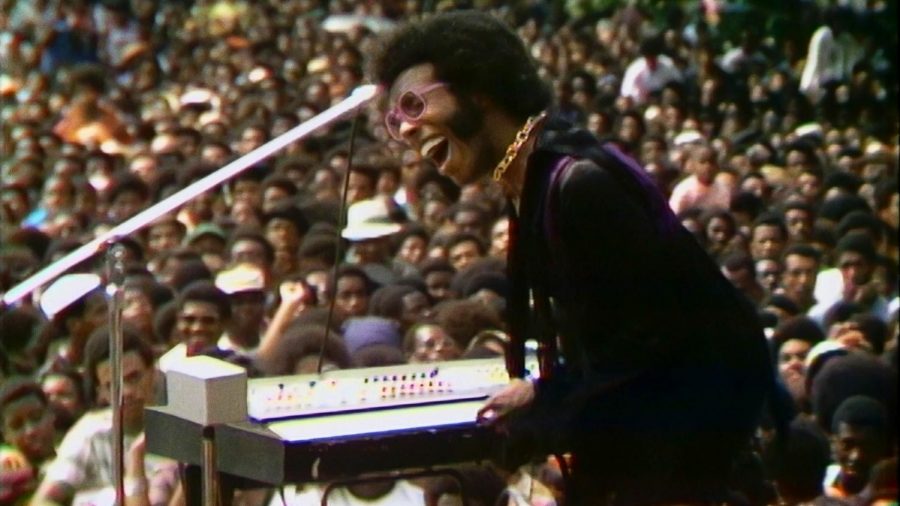

A still from “Summer Of Soul (Or, When The Revolution Could Not Be Televised)” by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson (Courtesy of Sundance Institute)

January 29, 2021

On Jan. 28, the first day of the 2021 Sundance Film Festival, Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson made his directorial debut with “Summer of Soul (…Or When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised).”

In the first few scenes of the film, there are a couple of text slides to give context to the rest of the documentary that read, “In 1969, during the same summer as Woodstock, a different music festival took place 100 miles away. Over 300,000 people attended the summer concert series known as the Harlem Cultural Festival. It was free to all. The festival was filmed. But after that summer, the footage sat in a basement for 50 years. It has never been seen. Until now.”

“Summer of Soul” is part concert documentary, part historical and cultural documentary. From the booming music industry and the moon landing to the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War, 1969 was a definitively revolutionary period.

History of Harlem

In 1969, Harlem was a hub of revolution and creativity. To capture and honor this thriving community, Tony Lawrence created the Harlem Cultural Festival with support from Mayor John Lindsay. This music festival featured headlining artists including Stevie Wonder, B.B. King, Sly and the Family Stone, The 5th Dimension, Nina Simone, The Staple Singers, Gladys Knight & The Pips and Mahalia Jackson, among many other artists and bands who were topping the charts in the late ‘60s.

As both a time of cultural revolution and social unrest, there was a growing fear that the summer of 1969 could devolve into violence. However, instead of violence, the Harlem Cultural Festival offered a chance for emotional release through the power of music. With the universal language of music, both artists and audience members alike could confront emotional turmoil, rage and trauma — but with music from prominent Black artists, there was a chance for catharsis and joy.

Harlem was a cultural melting pot, and people of Black, Cuban, Puerto Rican and Caribbean descent could find acceptance in spite of the violence that took place all around America. The festival offered a chance for collective grief over the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy and Malcolm X.

The Harlem Cultural Festival occurred for eight weeks throughout the summer of 1969. On July 20, Apollo 11 landed on the moon, but Harlem residents were more focused on the festival and they were more concerned about the poverty and inequality that they saw every day. Pointedly, the Space Race was criticized as a waste of money when plenty of Americans go hungry every day.

This festival was a chance for predominantly Black Harlem residents to join together and rejoice. It offered an opportunity to collectively reject the status quo while simultaneously celebrating Black pride and music.

“Summer of Soul”

“Summer of Soul” splices together scenes from artists’ groundbreaking performances, a lively dancing audience, life on the streets of Harlem and key historical footage of the civil rights movement. Music and politics have always been linked together, but this documentary argues that this forgotten festival offered the chance to heal from historical trauma whilst celebrating political wins and Black identity.

Just as Harlem was a cultural melting pot, the festival was also a musical melting pot. Various genres such as blues, folk, gospel, jazz, R&B, Motown and — of course — soul music were featured at the festival in a grand cross-section of cultural celebrations.

With such large headlining names and the cultural significance of this summer-long festival, it is shocking to think that such footage of the event was nearly lost forever. “Summer of Soul” features never-before-seen performances and interviews, but the fact that this footage was never widely released brings up topics of Black erasure and forgotten history.

In a Q&A after the film, director Ahmir Thompson shared that “literally all of this could have been discarded. It was about to be trashed, [so the making of the documentary] was meant to happen,” he said. The documentary is “all about experiencing joy,” and it raises the question, “Why was this not seen as important?”

To equate the festival to today’s era, producer Joseph Patel said that it would be “the equivalent of two Coachellas happening in New York City for free, with the biggest popular artists of multiple generations.” It is heartbreaking to consider the fact that this footage was nearly lost and this event could have been forgotten, but as the documentary features interviews with festival attendees and performers 50 years after the fact, the joy they feel is palpable across the screen.

The Harlem Cultural Festival was periodically referred to as “Black Woodstock,” but the fact of the matter is that this festival lasted over a more sustained period of time and featured more artists during the same summer as Woodstock.

With the premiere of “Summer of Soul” in 2021, it is impossible to refrain from drawing connections from 1969 to today’s era. Thompson said, “With the state of how things are now, it was not lost on us that the very circumstances that caused that concert to be in the first place with civil unrest, and then 50 years later, the same exact thing happening… Unfortunately, the timing was perfect.”

“Summer of Soul” is delightfully celebratory, emotionally heartbreaking, wonderfully revolutionary and a beautiful love letter to the music and people of the 1960s.